From Mammoths to Mediums

GA 350

IV. Effects of light and colour in earthly matter and in cosmic bodies

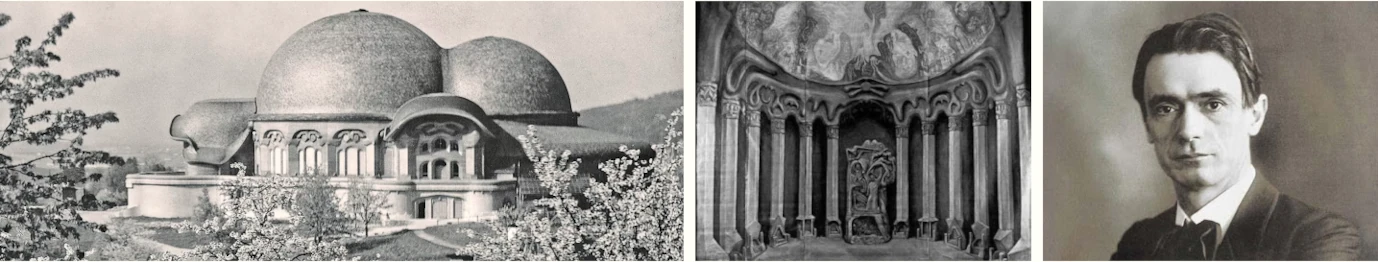

9 June 1923, Dornach

Well, gentlemen, what have you in mind?

Question: Various chemical substances have the property that they produce specific colours in a flame, for example. On the other hand many stars also have a bit of colour. Mars, for example. When iron oxidizes, rusts, you also get a reddish colour. Would these things be connected?

Rudolf Steiner: That is of course a very difficult question. One would first of all have to remember the things we have already discussed about colours.11See lecture given on 21 February in From Limestone to Lucifer (as in note 1). We have talked about a number of things relating to colours. You have to consider that the colour of the solid has to do with the whole way in which it exists in the world. Imagine, therefore, that we have some substance or other. This substance has a particular colour. Now I believe you're thinking this colour may look completely different in a given situation, for instance if we put it in a flame, so that the flame will then have a particular colour? We have to remember that the flame already has its own colour when it develops. If we put some material into the flame, the two colours interact, the colour of the substance and the colour of the flame. But it is altogether most peculiar how colours behave in the world. Let me tell you a few things about this.

You know the ordinary rainbow. It has a band of red, then the colour changes to orange and yellow, then it is green, blue, a somewhat darker blue, indigo blue, and finally the band is violet. We thus have more or less seven colours in the rainbow [Fig. 8]. People have always observed these seven colours which one gets in the rainbow, the most beautiful colours ever to be seen in nature. And you must also know that these colours are such by nature that they are floating freely. As you know, they develop when the sun shines somewhere and there is rainy weather between you and the sun. The rainbow will then appear in the sky on the other side. So if you see a rainbow somewhere you have to say: 'Where's the rainy weather? Yes, the sun must be on the other side of the rain, the side facing away from it.' That is how things have to be. That is how the seven colours of the rainbow develop.

But these seven colours also appear elsewhere. Imagine we are burning a metallic body, heating it more and more so that this metallic body gets very hot. As you know, it will first turn red hot, and finally white hot, as one says. Imagine therefore that we have created a kind of flame by having what is really, I'd say, a metal flame. But it is not a real flame, it is glowing metal, metal that is wholly aglow. If you look at a metal which is thus wholly aglow through a prism, as it is called, you do not see a white hot mass but you see the same seven colours as in a rainbow.

Let me draw you a diagram [Fig. 9]. Imagine this to be the glowing metal, and I then have such a prism here. You know what a prism is. Here it is shown from the side, such a triangular piece of glass. There's my eye. I now look through this. And then I do not see a white body but the seven colours of the rainbow in the order red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. Looking through the prism I see something that is really white, white hot, in seven colours. You see from this that it is possible to see something that is white hot shimmering in the colours of the rainbow.

Now we can also do something else that is most extraordinarily interesting. You see, we can only produce such a white hot mass if we heat a metal, or any solid body. But if I have a gas and burn up the gas, I do not get the seven colours looking through my prism, not such a band of seven colours, but something quite different.

Now you may say: 'How do we get such a glowing gas?' Well, it is quite easy to get a glowing gas. Imagine, for example, I have some ordinary table salt. There are two substances in it—a metallic substance called sodium, and then also chlorine. Chlorine is a gas and if you let it spread anywhere, if it is present anywhere, it'll immediately rush up your nose and it is biting. It is the same gas which people use to bleach their linen, for example. The linen is bleached if you let chlorine pass over it.

So if you have sodium and chlorine together, as a solid, this is the ordinary salt we use to season our food. If you take the chlorine away and put the sodium, which will then be whitish, into a flame, the flame will turn quite yellow. Why does this happen? Well, gentlemen, it happens because sodium turns into gas if the flame is hot enough, and the sodium gas will burn yellow, giving you a yellow flame. So now we have not only a glowing metal but also a gaseous flame. If I look at this through my prism, it'll not show seven colours but on the whole stay yellow. It is just at the side—and you have to take a very good look for this—that you see something a bit blue and a bit red [Fig. 10]. But one generally does not notice this but only sees the yellow. But all of this is not yet the really interesting thing. The most interesting thing is this. If I set the whole thing up [Fig. 9],12A few sentences are missing here. To show the 'really interesting thing', Rudolf Steiner probably described a set-up that would look something like this:

Using this arrangement, it is possible to see the yellow absorption line in the yellow part of the continuous spectrum of the incandescent lamp of which Rudolf Steiner then spoke. The drawing on the board was only a very rough sketch. and then put the yellow flame in here and again look through my prism—what do you think? You'll say: 'Looking through there I'll get red, orange, yellow, green and so on. And yellow, too.' 'It'll be a particularly strong yellow here,' you'll say, 'a particularly bright and luminous yellow.' But you see, that is not true. What happens is that to yellow appears at all, the yellow is completely eliminated, extinguished, and you get a black bit there.

Just as you can have a yellow gas flame so you can also have a blue one. One can find other substances, lithium, for example, that have a red flame. Potassium and similar substances give a blue flame. If you put a blue flame in here, for instance, the blue will not come up more strongly, but you'll again have a black spot. So the peculiar thing is that when you make something glow, if a solid body is completely aglow and is not a gas, you get this band of seven colours. But if you only have a burning gas, you get more or less a single colour, and this single colour then extinguishes its own colour in the band of seven colours.

These things I am telling you are something people have not known all that long; they were only discovered in 1859.13In 1859, Bunsen and Kirchhoff discovered spectral analysis. It was not until 1859 that it was found that if you have a band of seven colours coming from a glowing solid, then individual colours coming from glowing gases, burning gases, will extinguish the corresponding colours. You can see the highly complex way in which one colour influences another. And it is because of this that if one looks at the sun in the ordinary way, it looks as if it were a white hot body. It is really like this. If you look superficially through a prism, you'll also see the sequence of colours—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet—in the sun. But if you look more carefully, then you'll not have those seven colours in the sun's disc. The seven colours will merely be near each other, with lots of black lines in between, a whole lot of black lines. If you look very carefully at the sun you do not have a band of seven colours; you'll have the seven colours, but always interrupted by lots of black lines.

What does one have to say to oneself in that case? If it is not the usual, continuous band of colours that shines out from the sun but a band of colours with lots of black lines in between, well, then one has to say to oneself: 'There are lots of burning gases between us and the sun and these are always extinguishing their particular colours between us and the sun.' If I do not look at glowing metal, therefore, but at the sun, and see those black lines, I have to say to myself: 'There, always in the corresponding place, the yellow is extinguished by sodium, for instance. Looking into the sun and seeing a black line in the yellow, I have to say that there is sodium between me and the sun.' And I get such black lines for all the metals in the sunlight. So all kinds of metals exist as gases in cosmic space between me and the sun.

What does this tell us? Gentlemen, it tells us that cosmic space, or at least, in the first place, the area surrounding the earth, is filled with lots of metals that are not just glowing but burning. If one thinks about this one must altogether understand that basically we can never just say that we are standing here on the earth and up there is the glowing sun, for anything we see actually depends on what is there between us and the sun. And physicists would be most surprised if they ever actually managed to get into the sun, for it would not be as they expect. What we see actually comes from the things that are between the human being and the sun. So there you can see from just one example how complex the connection between substances and colours really is.

So if you have a flame somewhere and the flame, say a candle flame, has a particular colour, you must first of all ask: 'What does the candle contain?' Solids from the candle exist as gases in the flame; they are usually made into gases by the heat of the flame. If we then look through a prism, as I did here [pointing to the drawing]: when a substance is a gas it colours the whole flame. Sodium will colour the flame yellow, for example. If you had a flame somewhere, in this room, for example, and looked through a prism—the sodium is almost always black. You don't actually have to put it in first. If the apparatus is very exactly set up, so that you can see things properly, you'll always find these black lines that should really be yellow and basically develop because very small traces of sodium are present everywhere. This proves to you that sodium is altogether necessary in the natural world. We cannot live unless it is there. We must also always have a quite specific amount of sodium in us and have to process the sodium in us. Its presence is really only betrayed because it always extinguishes the yellow lines and makes them into black lines.

Now you need to remember what I have told you before.14See note 11. How do blue and violet colours arise? And reds and yellows? Well, blue, as I told you, is the colour of vast cosmic space, for there is nothing out there where we see the blue firmament. It is vast, black cosmic space. We thus see vast, black cosmic space. But we do not see it, though it is there right in front of our eyes. Water vapours are rising all the time between us and that vast, black cosmic space. Even if the air is pure, you always have water vapours in the air. So if this is the earth [drawing on the board], these are the water vapours, and all around is black cosmic space, the sun will shine through those water vapours. If you stand down here and look up, you do not see black but blue. You look through something that is illumined and therefore see dark space as blue. It means that if I see something that is dark through something that is illuminated, I see it in blue.

The red sky at dawn and dusk is, as you know, yellowy or a yellowy reddish colour. If this here [drawing on the board] is the earth, and there are the vapours all around, and now the sun comes up here, I see this illuminated. I see something that is lit up, but I see it through the dark vapours. This makes it yellow for me. When I see something bright through something dark it will be yellow. When I see something dark through something that is lit up, it will be blue. Blue is darkness seen through something that is lit up, yellow is the brightness seen through something dark. I am sure you can understand this.

If I have the yellow produced by the yellow sodium flame, this yellow colour of the sodium flame means that sodium is a substance that gets very bright when it evaporates but at the same time also creates something dark around itself. Sodium therefore really burns like this. If the sodium is burning here, the white light shoots up in the middle [Fig. 11, left] and I therefore see the whole as yellow. The sodium radiates light, but creates darkness all around it because it radiates light so powerfully.

It need not surprise you that sodium creates darkness around it by radiating such a powerful light. If you are a fast runner and run really fast, someone who wants to keep up with you will inevitably lag behind. The light spraying out is a fast runner; it therefore shows itself as shining in the darkness—it appears yellow to me.

With an ordinary candle flame the situation is that the particles go apart like this [Fig. 11, right]. This makes it light all around here and dark at the centre. So if you have an ordinary candle flame you see the darkness through the light. Here the bright little dots scatter; here at the centre it stays dark and therefore appears blue. If you have a yellow flame, therefore, as in the case of sodium, it means that it sprays out with tremendous power. If you have a blue flame this means that it does not spray out very much but goes apart and scatters.

That is the difference you always get in the world with the effects substances have. Imagine I have a glass tube here; I fuse it so that it is closed at both ends. I then also pump out the air so that I have a glass tube that has vacuum inside.15Geissler tubes, after Heinrich Geissler (1815-79), glassblower and mechanic. I then do the following. I let an electric current go in here, letting it go this far, and another current on the other side. This gives me a closed circuit. So the two poles of electricity are opposite each other here. Between them is a vacuum. And now something very strange happens. On the one side the electricity sprays out and on the other side, where it looks bluish, you get such waves [Fig. 12]. And that then goes together. Light is all the time spraying into the darkness, we might say, bright electricity into the darkness. So there you have the two flames I have shown you separately. You have this one at the one pole of the electricity and that one at the other pole. Here on one side you have the same thing as in the sodium flame, and here on the other side the same thing as in an ordinary candle flame. If one does this properly, one gets different kinds of rays here, including X-rays, which, as you know, can be used to see solid parts such as bones and so on, or foreign bodies in the body.

So the thing is that there are substances in the world that are radiant. Others are not radiant but, we might say, give off a faint light and cover themselves with such waves on the surface. Substances that cover themselves with such waves are bluish; substances that are radiant are yellowy. If a dark body then comes in front of the yellow the yellow will turn reddish. So if you make the yellowy light darker again it may turn reddish.

So you see, gentlemen, solid bodies in the world are such that some are radiant and therefore have the bright colours we see on one side of the rainbow; others are not radiant but send out those waves. This gives us the bluish colours from the other side of the rainbow.

If you know this you will say to yourself: 'There are many stars such as Mars, for instance, which is yellowy or reddish, or like Saturn which has a bluish light.' You are then able to see from this what the star is like, how it behaves. Mars is simply a star that radiates a great deal and therefore it has to appear yellowy or reddish. It is a star that radiates a lot. Saturn is a body that stays quieter and covers itself with waves. You can almost see the waves around it. When you have Saturn you can also see the waves as rings around it. It appears to be blue because it surrounds itself with waves. So the things we observe on solids here on earth tell us, if we are not dull in our minds but observe correctly, what the bodies are like out there in the universe. Only one has to know, of course, that the whole of cosmic space is filled with all kinds of substances, as I've told you, and these are really always in a state where they'll burn.

Take just one solid, iron for example. It rusts. I think that is what you meant with your question, isn't it? The iron rusts and therefore grows redder than it usually is. So we have a solid that is relatively dark, which rusts and then turns reddish. Having studied the colours we'll be able to tell ourselves what it really means that iron turns reddish when it rusts, which means when it is continually exposed to the air. Let us see clearly what this means. I don't have chalk in all the colours to hand, but you'll see what I mean. Let us assume, then, that we have blue iron. Now it is exposed to the air. And because it is exposed to the air it turns reddish as it rusts.

Now you can say to yourself that the reddish colour develops because something light is seen through darkness. If I look at iron in its usual state it is dark at first, which means it produces waves. But if I expose it to the air for a long time, if the iron is in contact with air for a long time, the air gets to the iron; and the iron gradually changes in the air for it begins to defend itself against the air. It defends itself against the air and begins to grow radiant. And something that radiates like our sodium flame here, so that you get darkness all around, will be yellowy or reddish. You are therefore able to say that the relationship between iron and air is such that the iron begins to be all on edge inside and grows radiant. The iron gets all on edge and grows radiant.

Now you know that iron is also present in the human body, where it is a very important substance. Iron is in the blood and it is a very important part of human blood. If we have too little iron in the blood we are people who cannot walk properly, getting tired quickly, people who grow lethargic. If we have too much iron in the blood we get excited and smash everything to pieces. We therefore have to have just the right amount of iron in the blood, otherwise we don't do well. Well, gentlemen, people do not pay much attention to these things today, but I have mentioned this to you before: if you investigate how the human being is connected with the whole world you find that in man the blood is connected with influences that come from Mars. Mars, which always moves, of course, really always stimulates the blood activity in us. This is because of its relationship to iron. Scholars of earlier times who knew this would therefore say that Mars had the same nature as iron. So in a sense we can regard Mars as something that is like our iron. But it also has a reddish yellow shimmer, which means it is all the time growing radiant inside. Mars we thus see as a body that is all the time growing radiant inside.

We only understand the whole of this if having made these studies we say to ourselves: Mars is iron-like by nature, is a substance rather like iron; but it is always on edge, wanting to grow radiant all the time. As iron does under the influence of air, so does Mars want to be radiant all the time under the influence of its environment. By nature it is therefore inwardly on edge all the time, wanting to come alive. Mars constantly wants to come alive. We can see this from the whole of its colouring and the way it behaves. With Mars we have to know that it is a cosmic body which really wants to come alive all the time.

It is different with Saturn. Saturn has a bluish light, that is, it is not radiant but surrounds itself with a wave element. It is exactly the opposite of Mars. Saturn all the time wants to go dead, become a dead body. One can see that Saturn is surrounding itself with brightness, as it were, so that we then see its darkness as a bluish colour through the brightness.

Now let me draw your attention to something. You can see something really interesting if you walk through a willow wood on a night that is not really dark but rather dusky—walking through a wood where willows grow. Every now and then you may see something that'll make you ask: 'Goodness, what's that light there?' You come close to it and the light can be seen to be coming from rotting wood. Something that is rotting down thus becomes luminous. If you then walk a long way off and look at it again, with something dark behind this luminous stuff, it would no longer appear to be luminous but blue. And that is how it is with Saturn. Saturn is decomposing. Saturn is really decomposing all the time. Because of this there is something of a brightness all around it, but the star itself is dark, and it looks blue to us because we are looking at its dark shape through the decomposing matter which is all around it. So we see that Mars wants to live all the time and Saturn wants to die all the time.

This is what is so interesting, that we can look at cosmic bodies and say: 'The cosmic bodies which appear to have a bluish shimmer are perishing, and those that appear to have a reddish, yellowy shimmer are only coming into existence.' And that is how it is in the world. In one place something is coming into existence, and in another something is passing away. Just as on earth you have a child in one place, and an old man in another, so it is also in space. Mars is still a young man who wants to be alive all the time. Saturn is already an old man.

You see, the ancients would study this. We'll have to study it again. But we'll only understand what the ancients meant if we find it again for ourselves. Because of this it is really silly—I spoke of this also the last time—for people to say that in anthroposophy we are simply writing up all the things that can be found in the ancient writings. For you cannot understand the things you find in ancient writings! You see, one only understands the things written in the ancient works, which are based on real wisdom, if one has first found them again for oneself. There was a verse known in medieval times, before America was discovered, that was most interesting.16Often quoted in alchemical literature and said to have been composed by Basilius Valentinus, said to have been a Benedictine monk at St Peter's monastery in Erfurt, Germany, around 1413. A version of it is published in Gesammelte Schriften des Basilius Valentinus, Hamburg 1740. Almost every single person would say it. In medieval times all kinds of people would say the verse, for they would learn it then the way people today learn—well, I don't know—an agitators' slogan perhaps.

The verse goes like this.

O Sun, a king of this world!

Luna keeps your generations going.

Luna is the moon.

Mercury soon couples you.

Without Venus you'd all be nothing,

Venus who chooses Mars to be her husband.

So the verse suggests that Venus, another young figure, has chosen Mars for her husband. It is suggested that Mars is a young man out there in the universe.

Without Jupiter's might you'd lack everything.

It is therefore suggested that Jupiter gets busy everywhere. And then, in the end, we have:

So that Saturn, ancient and old

may show himself in many colours.

Just think how beautifully this medieval verse contrasts Mars' youth with Saturn's age.

O Sun, a king of this world!

Luna keeps your generations going.

Mercury soon couples you.

Without Venus you'd all be nothing,

Venus who chooses Mars to be her husband.

Without Jupiter's might you'd lack everything.

So that Saturn, ancient and old

may show himself in many colours.

So you see it is something one can't understand, and people show this. For a present-day academic reading such a verse would say: 'Well, that's just silly superstition.' He'll laugh about it. And when one rediscovers the truths that lie in such a verse, he'll say one has copied it. Yes, well, you know, it is quite unbelievable how stupidly people behave really, for they cannot understand it, of course. No academic today understands what is said in such a verse. But if you are able to do spiritual research, you'll discover it again, and then you'll finally understand it. One has to find these things out for oneself again, otherwise the ancient verses, which are popular wisdom, really have no value at all. But it is also a wonderful thing when one discovers these things through spiritual research, and then finds this tremendous wisdom in simple popular verses. It shows that the old popular verses were taken from things taught in the ancient schools of wisdom. That is where the verses come from. Today people can no longer go to their academic scholars in that way, for today's knowledge does not give us any verses! You won't find much that is of use in life. But there was a time when people did know things like these, which I have also told you again today. They then put them into such nice verses. And then all kinds of things came of this, of course, and sometimes also misunderstandings. Now the verse about all the planets that I've just recited for you has been forgotten. But other verses later came to be distorted.

Now it is of course also true that it means something when animals do something or other. They are connected with the universe. We can know that something is happening with the weather if we look at a tree frog. You know, tree frogs are used as weather prophets when they move up or down their ladder. This is because all that lives is connected with the whole universe. Only it came to be distorted later, and then there is perhaps also some justification in having verses to amuse oneself, having listened to some that have been taken hold of by silly minds. So if someone says, for example: 'When the cock on the dunghill does crow, the weather will change or it'll stay as it's now,' well, it just shows that one should not mix everything up together, and not mix in silly things with wisdom. The verse I cited does of course point to secrets in the universe that have to do with light and colour. The things people often say about a cockerel or the like are, of course, something we can laugh about, like the saying I have just quoted. But on the other hand old country maxims sometimes still have something extraordinarily deep to them, something most wise, even today. And it is not for nothing that a countryman is unhappy if it snows in March, for there simply are connections between seed grain and March snows.

We thus truly see from such things that we can understand the whole world in the light of the things we observe on earth. It would perhaps be better if one stuck more to what the tree frog is able to do as it climbs up and down, depending on the weather, rather than to what a dormouse does when it sleeps and sleeps, so that one sleeps through all the secrets of the universe.

I hope you've been able to understand what I have been talking about in answer to your questions. It is of course quite complicated and one cannot put it in just a few words. I therefore had to say all those things, but you'll be able to put it together. It really is quite interesting, isn't it, to see how things go together in this way.

We'll continue on Wednesday.