From Limestone to Lucifer

GA 349

IX. Why do we not remember earlier lives on earth?

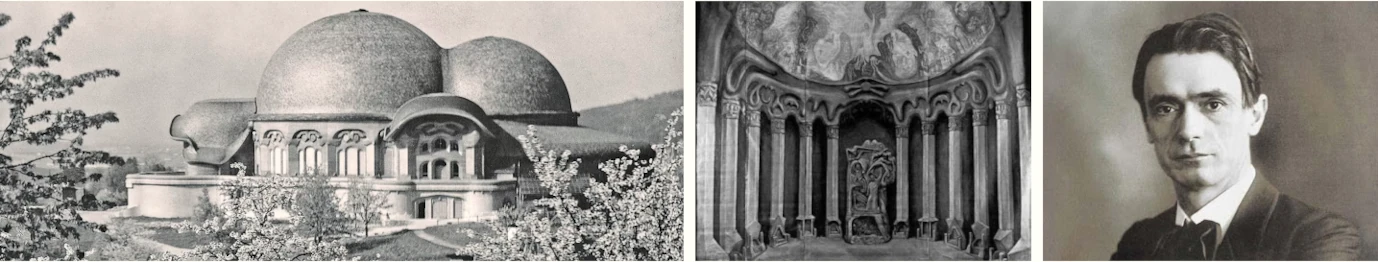

18 April 1923, Dornach

Good morning, gentlemen! Let us now add some more on the matter we have been considering. As I said at the end of our last meeting, the main objection people raise is that the things they hear about life before we enter into an earthly body and also about earlier lives may indeed be true—but why do they not remember any of it? The first thing I'll do today, therefore, will be to show you in detail why we don't remember and what memory is about.

To start with we have to give some thought to the human body, for it really is indeed important to put these things in a scientific way.

You see, in this respect, when it comes to the question of repeated earth lives, people are really quite funny in the way they judge others who did or do know something about these repeated earth lives. A great figure in German literature was Lessing, who lived in the eighteenth century.31Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim (1729-81), German writer. Lessing's achievements were tremendous, and he is still generally acknowledged to this day. Professors speaking about Lessing at German universities will often stay on the subject for months. As you know, a book by a Lessing expert has actually appeared in social-democratic literature, a big book on Lessing by Franz Mehring.32Mehring, Franz (1846-1919), German left-wing writer, one of the founders of the German Communist Party. Wrote historical studies of the workers' movement.He presents Lessing from a different point of view. We can't say that what he says is right; but at any rate, social-democratic literature now includes a big book on Lessing.

In short, Lessing is considered a very great man. As a very old man Lessing, whose plays are still performed at many theatres and much appreciated, wrote a relatively short work called 'Educating, or bringing up, the human race'. At the end of the book we read that we really won't get anywhere in considering the human soul, that we really cannot have proper knowledge of the inner life, unless we assume there to be repeated lives on earth, and if we reflect on this, we really come to see things the way primitive peoples did in the past. For they did all believe in repeated earth lives. Humanity only gave this up later, when people became 'modern'. And Lessing said that he could see no reason why something should be nonsense just because people believed it in earliest times. In short, he himself said he could only manage with the inner life of man if he held to this original belief in repeated earth lives.

Now as you can imagine, this is highly embarrassing for present-day 'scientists', as they are called. They will say: 'Lessing was one of the greatest people of all times. But those repeated earth lives were nonsense. What is one to do with this? Well, Lessing was old then. He'd grown feeble-minded. We don't accept the repeated earth lives.' You see, that is the way these people are. They will accept the things that suit them and call the person concerned a great man. But if he ever said anything that does not suit them, then they say he was feeble-minded at the time.

Very odd things will sometimes happen. There was the great scientist Sir William Crookes, for example.33Crookes, Sir William (1832-1919), OM, bom in London, chemistry lecturer at Science College, Chester.. Well, I don't agree with everything he says, but he is certainly considered to be one of the great scientists. He lived in our time, at the end of the nineteenth century. He'd always do scientific work in the mornings. He'd go to his laboratory, and he made great discoveries. We would not have some of these things—X-rays and so on—if Crookes had not done the preliminary work. In the afternoons, however, he would always study psychology. As I said, I do not agree with everything, but that is what he did. And surely people thus also had to say: 'Well then, he must have been intelligent in the mornings and stupid in the afternoons—bright and stupid at the same time!' That's the way things are in the world.

Now there's something else. You will always hear—I spoke about this when I was talking about the colours—that scientists consider Newton to be the greatest scientist of all times. He wasn't, but they think so. And again we have an embarrassment. This man Newton, considered the greatest scientist, also wrote a book on the Book of Revelation,34Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St John, published posthumously, London 1733. which is usually found at the end of the Bible. Another embarrassment, therefore.

In short, people who altogether deny that it is possible to study the psyche, the soul, are profoundly embarrassed by the greatest scientists of all people, and also the greatest historians. The point is that anyone who takes science really seriously cannot help himself but to extend his search for knowledge also to the soul. And the opportunities for this are always given. As I told you, one simply needs to observe. Now it is not possible to see everything directly by looking at everyday life, especially if one has not studied it beforehand. Nature, and sometimes humanity, also does experiments for us, experiments we need not design artificially. Once they have been done, however, we can study them. We can take our guidance from them, or at least pick up ideas. There is one experiment that is really important, characteristic, if we want to have something valid concerning the inner life of man. Everyone accepts the physical body, otherwise they would have to deny existence to the human being altogether. It is not in dispute. Everyone has it. In modern science the view is that the physical body is the only one, and everything has to be explained in terms of the physical body.

There is something, however, which will immediately show us that the human being also has the other three bodies—the invisible ether body, the astral body and the I—if we observe it properly. One thing can be observed in a completely scientific way—there are many things, but one in particular can be observed in a completely scientific way. It shows that human beings may indeed get into states where they show us that the ether body exists, and the astral body, and the I.

You see some people in Europe feel the need to numb their minds. Many other means are used today. I have told you that people use cocaine, for instance, to numb their minds.35Cocaine, a white alkaloid extracted from the leaves of the South American coca shrub (Bolivian leaf from Erythroxylon coca or Peruvian leaf from E. truxillense). But opium has been used in Europe at all times. There have always been people who have been dissatisfied with life, or had too many problems, not knowing what to do, and they would drug themselves with opium. They would always take just a small amount of opium. What happened then? To begin with, if someone takes a small amount of opium he gets into a state where he experiences things inwardly; he is no longer thinking, but begins to dream, seeing wild, chaotic images. He likes it, it puts him at his ease. The dreams get more and more intoxicating. Some will then enter into blank despair, bethink themselves and begin to behave like sinners; others start to rant and rage, even feeling murderous. And then they go to sleep. Taking opium thus means that people take a poison into their bodies so that they enter vehemently into a state which then gradually merges into sleep.

If we consider what is really happening here in the human being we find—one can see it—that they first of all get into very excited dreams, starting to fantasize, and then go to sleep. So something has gone away from them. The element has gone away from them that makes them sensible people, something that lives in them to make them sensible. That has gone. But before it goes, and even after it has gone, they live in the wildest, most chaotic and excited dreams. After a time they'll wake up again and be restored to normal, up to a point, until they take opium again. They thus make themselves into sleeping people, but vehemently so.

We can see that when someone goes to sleep under the influence of opium the principle that is active in him is not the one that makes him sensible but the one that gives him life; otherwise he would not wake up again, he would have to die. The principle is active in him that gives him life for the moment. And we can see that during the night, too, something of a struggle takes place in the body so that we may wake up again. Something is active in the human being that does not include the sensible part; it is the element that gives life to the body. The poison makes the person's body die a little. This drives away common sense. But the life-giving element is still in him, for otherwise he would not wake up again. What has therefore been influenced by the opium? The principle that gives life. Taking small amounts of opium has influenced the ether body.

But now imagine someone takes too much or deliberately poisons himself with opium. The effect is not the same then. It is a strange thing, but now only the thing which happens last when a little opium is taken will happen. What happens last in that case will come first if a lot of opium is taken. The individual will immediately go to sleep. The principle that gives one sense will not go away slowly then, but quickly, very quickly. Something remains in the person, however that was not in him at all when he took just a little opium. Again this is something we can see.

So let us assume someone takes so much opium that he is really poisoned. The first thing that happens will be that he goes to sleep. But then the body will begin to get restless, unreasonable; he is breathing stertorously, snoring; then he'll have fits. And you'll notice something very peculiar, for his face will be quite red and his lips quite blue. Now remember what I told you last time. I said that breathing problems always come when we breathe out. Now what is snoring, for instance—first stertorous breathing, then snoring—what is it really? You see people who cannot breathe out properly will snore. When we breathe out properly—if that is the mouth [Fig. 23], then the air goes in, and after some time it goes out again. And in the air passage is the uvula. You can see it if you look in the mouth. And up there is something that goes up and down, the velum, the soft palate. This moves. The uvula and the soft palate are moving all the time as we breathe in and out, if it goes normally. But if you breathe in and then do not breathe out properly, so that it eructs, then this part, the soft palate and the uvula, starts to tremble and this produces the stertorous breathing and then snoring.

You can see from this that it has something to do with our breathing. Someone who just drugs himself with a little opium gets into those other states I have described to you—a kind of delirium, a rage. He will slowly go to sleep. But if he goes to sleep quickly, having taken a large amount of opium, he starts snoring and gets fits; his face turns red, his lips blue. For as I told you, human beings have red blood because they breathe in oxygen. When the blood mixes with oxygen it turns red; when it mixes with carbon it turns blue. When it is breathed out, it is blue. So if you see someone with a red face and blue lips, what does it mean? Yes, there is too much breathed-in air beneath the face, too much red blood because of breathing in. And what does it mean when the lips are blue? Then there is too much of the blood that should really go out. It piles up in there. It could indeed go on to the place in the lung where the carbon dioxide then comes free, where carbon dioxide can be breathed out. So when someone is poisoned by opium the situation is that the whole of his breathing is held up. And because of that you get the red blood in the face on the one hand and the blue blood in the lips on the other.

This is tremendously interesting, gentlemen. What are the lips? You see, the lips are highly peculiar organs in the face. To have a face you really need to draw it like this [Fig. 24], with skin on the outside everywhere. It is covered with skin on the outside everywhere. But on the lips it is really a piece of inner skin. There the inner becomes outer. It is a piece of inner skin. The human being opens up his inner nature to the outside by having lips. If the lips are blue, therefore, rather than red, it means that everything inside has too much blue blood in it. So you see that when someone has opium poisoning the body sends all unused blood to the surface, and sends all blue blood to the inside.

This is something else primitive peoples once knew, this business of the blue blood going inside. When someone had too much blue blood inside they would say that someone who has too much blue blood inside him is in the first place someone who has little soul; his soul has gone away. 'Blue-blooded' therefore became a term of abuse. And when members of the nobility were called blue-blooded, people wanted to say their souls were not there. It is strange how these things live in a most marvellous way in popular wisdom. You really can learn a tremendous amount from language.

You can now see that this is something that has an effect in the human being but not, for instance, in a plant. For if you introduce a poison into a plant, the poison stays up above in some way; it does not spread. Belladonna, deadly nightshade, is a very poisonous plant. It keeps its poison up above and does not let it go into the whole plant. When a human being takes such a poison the effect is that it involves the whole body, driving the red blood to the outside and the blue blood inside. Yes, plants also have life. Those plants have their ether body in them, they have the principle in them which in people is left blue with small amounts of opium taken, not with large amounts. That will make the human being sentient. If a plant had blood it would also be sentient, as human beings are and animals. Humans and animals have this without taking opium when the ether body is in conflict with the physical body; the blood is then immediately pushed to the outside, and something remains behind in the body, and this puts things out of order in the body. This is the astral body. We are thus able to say that the astral body is influenced when much opium is taken.

The third way of taking opium is widespread in the world, though not in Europe—more among certain Turks, for instance, and above all in Asia and Indochina, among the Malays. These people always only take as much opium as they are just able to tolerate and therefore wake up again properly and do not die of it. They therefore go through everything opium eaters go through, which is most interesting. Only they gradually get habituated, and then they go through the process more consciously. The Turks thus say: 'Yes, I was in Paradise when I had taken opium.' So that is indeed how it is when the fantastic developments come. And the Malays in Indochina would also like to see all this. They therefore get the opium habit because they would like to see it all. This is something people can do for a relatively long time and we therefore have to say to ourselves that there must clearly also be something else.

Now one would have to say that if these people who eat opium from habit—it is a real habit with them—if these dreamers were to see only this they would surely get tired of it after a time. But, you see, it is a most peculiar thing. These people are descended from the first people on earth, people who still knew something of the eternal soul, the soul that goes through different lives on earth. They knew something of this. It is something people have lost today. And these people who have not gone through European civilization use opium to put themselves in a position where they can feel something of the soul's eternal life. It is indeed a terrible thing, but they will again and again induce a disease in themselves. At the present time a healthy body cannot know anything of the soul's immortality unless a person makes special mental efforts. And because of this these people are gradually ruining their bodies, so that the soul principle is gradually forced out.

You can see something very peculiar when you look at people who take opium habitually and therefore also survive for a time. They grow very pale after a time. They may have had a good skin colour earlier on, but now they will be pale.

It means something different among Malays than it would among Europeans, for they are yellowy brown and therefore really look like spectres when they grow pale. Then, after some time, they look as if their faces were quite hollow around the eyes. They then begin to grow skinny, and even before that will no longer be able to walk properly. They merely hobble along. Then they also no longer want to think and grow extremely forgetful. In the end they have a stroke.

[writing on the board]

Physical body—

Ether body—taking small amount of opium

Astral body—taking small amount of opium

I—habitual use of opium

Those are the phenomena. It is very interesting to observe it. Before their limbs grow clumsy they get severe constipation, which means their intestines are no longer functioning. You can see from the things I have told you that the whole body is gradually undermined.

Now there is something highly peculiar here. Not much is known yet about this because people do not pay attention to it; but it is something one can see quite easily. It is well known how these people become opium eaters; that has been described often enough. But now just let them try—after all they try things out often enough in other respects today—and give the dose a habitual opium eater takes to an animal. The animal will either get a little bit lively, which would be the first stage, where the ether body is thrown into chaos, or it will get to the second stage, if given enough, and die. You do not get the condition I have just described, the condition of the habitual opium eater, in animals. You do not get this in animals.

What does this tell us, gentlemen? Well, it shows that when opium in that strength gets into the astral body, causing the relationship between blue and red blood to change, the situation is that in animals blue and red blood are all the time shooting one into the other in a horizontal direction. In a human being, who learns to walk upright, blue and red blood does not exactly shoot in that direction [drawing on the board], but from top to bottom and from below upwards. It is because of this that human beings can be habitual opium eaters.

Now I have been telling you that human beings have an I because they are upright. Animals do not have an I, for their backs are horizontal. So what is affected by habitual opium eating?—the I. We are thus able to say: I—habitual opium consumption. And by considering opium we have now discovered all the three supersensible human bodies—the ether body with opium taken in small amounts, the astral body with opium taken in large amounts, and the I with opium taken habitually. So you see how one can develop this most beautifully in a scientific way; one must only be able to observe properly.

You'll now also see that a Malay who is a habitual opium eater comes to something tremendous. He comes to the I. And what does he get? What is this Malay or this Turk looking forward to as he follows his opium habit? He looks forward to it because his memory comes awake in a most wonderful way. He will quickly get a view of his whole earth life and much more. On the one hand it is terrible, for he is making his body sick by doing this. But on the other hand the desire to get to know the I has such a powerful effect in him that he just cannot resist. He is simply delighted when this gigantic memory is produced.

But, you see, it is like this. When someone does something to excess it will ruin him. If he works too much it will ruin him; if he thinks too much it will ruin him. And when someone is all the time calling up a tremendous power of memory, this will ruin his body. All the things I have described to you simply come from a memory that is too powerful. That is what comes first. And later—I have described it to you—the person grows slack in his walking. He no longer remembers inwardly how he should put his feet forward. This is unconscious memory. Then he grows forgetful. And it is exactly in achieving his aim that he is ruined. But it is possible to see, to be aware, that the I is present when opium has become a habit.

What happens in modern science? Well, if you open a book you will find the things I have told you. You find it said that people grow delirious with small doses of opium, and so on, and if they take large doses they will first go to sleep and their bodies will immediately be destroyed. They die, their faces having turned red and their lips blue. And all these things also come with habitual opium eating. But all this refers only to the physical body and what happens in it. You can read that opium eaters develop stertorous breathing, get fits, snore. You can read that they lose weight, are no longer able to walk, grow forgetful and finally have a stroke, because their memory is destroying the brain—for that is how we should see it. Everything is described, but it is all related to the physical body.

And that is nonsense, of course. Otherwise everything physical could only be said to relate to the physical body. All the phenomena that appear there can also be seen in plants. Yet we cannot say that man is just a plant. For with opium taken in high doses the effect shows itself in the astral body, and the phenomena relating to habitual opium use are only seen in human beings. If animals had something to gain from opium use and did not die of it immediately you would see many animals simply eating the opium found in plants. Why would they do so? Because animals eat the things they eat from habit. So if opium eating would benefit them, they would eat the opium in plants. If they do not do so, this is simply because they would not gain anything by it.

All this can be discovered by means of science. But we now have to consider if all this—the memory a Malay gains by making himself sick—can also be gained in a healthy way. Here we must remember that the earliest people knew that human beings live on earth again and again. Lessing said, as I told you, that he could see no reason why something should be nonsense just because people believed it in earliest times. Those early people simply did not have the kind of abstract thinking we have today. They did not have science either. They saw everything in mythological terms. Looking at a plant they would not study it and say that there were particular forces in it; they would say that it had particular spiritual elements in it. They saw everything in images and they were altogether still living more in the spirit ... [gap in text]. The situation is that human beings were then able to develop in such a way through progress that they came to live more in the physical body. This alone made it possible for them to be free, otherwise they would always have been influenced. The people of earliest times were not free; but they did still see things in the spirit. The way we are now, gentlemen, we do truly have the abstract ideas in which we are drilled even at school. You see, we are actually able to say that the most important activities of which humanity is so proud today are really something abstract.

Speaking to the teachers who are here in Dornach I said yesterday that when a child gets to be about seven years old he is supposed to learn something. He should learn, having learned his whole life up to now, that the individual he sees before him is his father and that this [writing f a t h e r on the board] means 'father'. He is suddenly supposed to learn this. But it has no connection with his father. Those are strange signs that have nothing at all to do with his father! The child is supposed to learn it all of a sudden. He'll resist, for his father is a man who has that kind of hair, such a nose; that is what the child has always seen. He'll resist the notion that those signs are meant to be his father.

The child has learned to exclaim 'ah!' when he was amazed. Now he is suddenly expected to think that this [pointing to the letter] is an 'a'. The whole thing is completely abstract and does not relate to anything the child has learned until now. So we must first build a bridge, so that the child is able to learn such a thing. Let me show you how such a bridge may be built.

You may, for example, say to the child: 'Look. What's that?' [Fig. 25, left]. If you draw this for the child and ask him what it is, what will he say? He'll say: 'A fish! That's a fish.' He'll not say, 'I can't tell what it is.' There [the written-down f a t h e r] he can't say: 'I can tell it's my father.' But he will recognize the fish.

I then say: 'Say the word fish; then leave out the "i" and what comes after it, and say just "F". Look, let me draw it for you: F.' I have thus taken the F from the fish. The child will first draw a fish and then come to the letter F. You just have to do it in a sensible way so that it'll not be abstract but come out of the image. And then the child will of course be happy to learn. It is something we can do with every letter. You just have to gradually get into the way of it.

One of the teachers at our Waldorf school once showed most beautifully how Roman figures came into existence. When he got to the V, it suddenly would not work. How can one get the V? Well, just look—what is this? [He held up his hand.] Of course you'll say that a hand is always a hand. But surely we can see something in it? I, II, III, IIII, V fingers. Let me draw this hand on the board [Fig. 25, third form] in this way, with two things extended [the thumb and then the other four fingers]. Now I have a hand with the V [five] in it; it is definitely a five. I now draw it in a slightly simpler form and you have got the Roman figure V from a hand that has five fingers.

So you see, gentlemen, the situation is that we are suddenly thrown into a completely abstract world nowadays. We learn to write, we learn to read, and it has nothing to do with life. And that is how we have lost the things which people had who were not yet able to write and read. Now you should not do as our opponents do and say: 'That man Steiner told us in class that people were more intelligent when they did not yet have writing and reading.' And they'll immediately go on to say: 'He does not want people to learn to write and read any more.' That is not my intention. People should always keep pace with their civilization, and certainly learn to write and to read. But we also should not lose the things that can indeed be lost through writing and reading. We need to take the spiritual view to discover what human life is like.

Let me now tell you something quite simple about two people. One of them takes off his shirt collar when he undresses at night—it has two little studs, one at the back and one in front, and I am taking this example because I am wearing such a collar. One of the two people does it without giving it any thought, undoing one stud and then the other and getting into bed. In the morning he'll run around and look everywhere in the room, asking: 'Where are my collar studs?' He cannot find them. He does not remember where he put them. Why? Because he did not give them any thought.

Now the other person. He has not exactly developed the habit of always putting his collar stud in the same place—which would be the lazy way—but he says to himself: 'When I put the little studs down, I put the one next to the candlestick and the other one over there.' He thus gives the matter some thought and does not merely put them down in a thoughtless way. Now when he gets up in the morning he'll go straight there, pick up the studs from where he put them, and have no need to hunt for them all over the room: 'Where are my collar studs? Where have I put my collar studs?' So what is the difference? The difference is that one man has given a matter some thought and then remembered, and that the other man did not give it any thought and does not remember. Now you can only remember things in the morning—it is no good to go to bed at night and then try and remember—you will only remember things in the morning when you have given them some thought the night before.

Gentlemen, let us take a bit of a look at history now. According to what I told you before, all our souls have been here at a time when only few people had as yet learned to think. People did not think at all in earlier times. In earliest times they lived in the spirit. And it was abnormal for someone to think in those times. During the Middle Ages people did not yet think at all. They have only started to think from the fifteenth century onwards; they did not take everything into their thoughts the way we do. This can be proved by historians. No wonder then that you don't remember your earlier lives! Now people have learned to think. We are at a time in historical evolution when people have learned to think. And in their next life they will remember this present life just as someone remembers his collar studs in the morning.

It means that if someone now learns to think of the things in the world in the right way, learns to think the way I have shown you, it will be just as it is when he thinks of his collar stud. The modern way in science is a way where people do not think of their collar studs. If someone just gives a description: 'Delirium develops, the lips turn blue and the face red,' and so on, the situation is that in his next life he will not think of the things that are most important. He'll not remember at all, throwing everything into confusion, like the person who creates confusion in his room because he has to go out and he cannot find his things. Someone who thinks, however, that it simply comes from ether body, astral body, I, will learn to think in such a way that he will be able to remember properly in his next life on earth. It will only show itself then. And today only few people are instructed on how to do things because only few individuals have known about it in their last life on earth. They now find out about it and are able to tell others about it. And if they do the things I have written in my books, if they do what it says in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds, it may happen that they realize even in this life that they have lived earlier lives on earth. But we are only just beginning with the anthroposophical science of the spirit. And people will gradually be able to remember again.

Now people will say: 'Yes, but one can't remember it; and if someone does not remember earlier lives on earth this means he cannot have had those earlier lives on earth.' We might just as well also say: 'A human being is unable to do sums; we can prove that a human being cannot do sums. He is a human being but he cannot do sums.' And to prove it someone brings in a four-year-old child and shows that the child cannot do sums. This is a human being, but he cannot do sums! We'll tell him: 'He'll learn, never fear. Knowing human nature we know that he'll learn to do sums.' And if someone refers to someone today who cannot remember his earlier lives on earth we have to tell him: 'Yes, but nothing was done in the past to help people remember. Quite the contrary, there are still many people today who have not caught up with the times, and they want to keep others in ignorance, so that they will know nothing of the spirit, have no idea as to what they should remember in their next life on earth, and get quite confused, like the man with his collar stud.' People must first of all learn to think in life about the things they should remember later on.

Anthroposophy exists to draw people's attention to the things they should later remember. And people who want to prevent anthroposophy actually want to keep people in ignorance, so that they will not remember. And it is important, gentlemen, for us to realize that human beings must first of all learn to use their thoughts in the right way. Today they want to define thoughts and demand that books should give the right definitions. That is something people knew even in ancient Greece, gentlemen. There was someone then who specially wanted to train people in making definitions. Today they tell you in school: 'You have to learn: What is light?' I knew a boy at school once; we were in primary school together, then I went to another school and he trained to be a teacher at a teachers' training college. I met him again at the age of 17. By then he had become a real teacher. So I asked him: 'What did you learn about light?' He said: 'Light is the cause of the ability to see bodies.' Nothing wrong with that. We might just as well say: 'What is poverty?' 'Poverty comes from having no money!' It is more or less the same kind of definition. But people have to learn a great deal of such stuff.

Now there was someone in ancient Greece who made fun of that kind of clever learning even then. Children have learned at school: 'What is a human being?' 'A human being is a living creature with two legs and no feathers.' A boy who was a particularly sharp thinker took a cockerel, plucked it, and brought the plucked cockerel to show his teacher the next day, saying: 'Sir, is that a human being? It has no feathers and has two legs!' That was the power of definition. And the things we generally still find in our books are more or less in line with such definitions.

All books, including social books people write, refer to the condition of life more or less the way a definition is made: 'A human being is a living creature with two legs and no feathers.' Further conclusions are then drawn. Of course, if you have a book with a definition to start with, you can draw all kinds of logical conclusions; but it will never fit the human being; it may also be true for a cockerel that has been plucked. That is the way our definitions are! What matters is that we must see the thing the way it really is.

The truth of the matter is that we have to say [referring back to the table of the human bodies in relation to opium use]: physical body; ether body, affected by opium taken in small amounts; astral body, affected by large amounts; the I affected by opium taken as a habit. And working with the science of the spirit, getting to know the human being in a way one does not merely describe things as if in a dream: 'Such and such conditions occur,' but really knows: 'That is where the astral body is active; there the ether body is active; in there the I is active,' one has real thoughts and no just definitions. And if we have taken in real thoughts in our present life on earth and not just definitions, we will remember the present life on earth in the right way. Now it is only possible to remember earlier lives on earth with great effort, as I have described it. Later we shall remember it well, if we do not make ourselves ill, for instance by taking opium, if we do not influence the body, but do exercises in mind and spirit that will make it possible for the soul truly to know the spirit.

So you see that a science of the spirit is in fact developing in anthroposophy. You can be sure that in anthroposophy we are not wanting to be superstitious. You get people who hear something unusual reported about spiritualistic things and they'll then say: 'Surely it is as if a world of the spirit is revealed in this.' But the world of the spirit reveals itself in the human being! If people sit around a table and get it to knock they'll say: 'There must be a spirit in there.' But when four people are sitting there, you have four spirits! You only have to get to know them. But people prefer to do things unconsciously. A medium has to be there. Just look at the newspaper cutting you gave me a few weeks ago, for example.36It has not so far been possible to trace this newpaper item. There you read that somewhere in England people got tremendously excited because things fell off shelves during the night, windows got broken, and so on. What struck me most about this—one must of course have seen it for oneself before one can really talk about it—but what struck me most was that the report also stated that those people had a whole horde of cats. Well, if you have a horde of cats and two or three of them run riot, you can indeed see these 'spiritual phenomena' happening. But, as I said, one would have to know the story properly; only then can one really speak about it.

You see, people once urged me strongly to attend a spiritualist seance. Well, I said I'd do so, for you can really only judge such matters if you've seen them. Now the medium was very famous, and when everyone had sat down, and had first had their minds numbed a bit by some music—everyone sat there numb in mind—the medium started to have flowers come down out of the air all the time, just the kind of thing one would expect. Every medium has an 'impresario', a manager, which is part of being a proper medium. Well, the people paid their obolus, a financial contribution, having had their enjoyment. For the organizers this was of course the important thing, that a contribution was paid. And I said—people are terribly fanatical about these things, they'll start a fight with you if you want to tell them the truth, it is just people like this who are the worst—but there were some who had sense and I said to them they should investigate things on another occasion, not at the end but at the beginning, and they would find the flowers in the manager's humped back. You'll always find that this is how things are.

Superstition has to be left behind, gentlemen, if we want to speak of the world of the spirit. One should never be deceived, not by mad cats nor by a hump-backed manager. We only find the spirit if we no longer fall for superstitions but always do things in a truly scientific way.