From Limestone to Lucifer

GA 349

VI. Essential human nature—physical body, ether body, astral body and I

4 April 1923, Dornach

Gentlemen! In modern science, only the things one can see with one's eyes, touch with one's hands are accepted. It needs an extra faculty to explore the things one cannot see with one's eyes, touch with one's hands, and people are not willing to work so that they may gain this faculty. Medieval knowledge based on faith meant that people had knowledge, a science, of all things that are of the earth, and they had a dogma of faith in what is written in scripture. People still hold this view today. They no longer want to venture beyond and gain knowledge that cannot be immediately apparent, for they have not really gone beyond a science of things that are tangible. I'd like to explain what I have been saying a little bit more by speaking of something that is quite old in present-day terms. But the really important developments relating to the subject actually came in the last third of the nineteenth century. All I have to do is to read to you the last sentences in a book and you'll see right away how modern scientists think in this respect. It says: 'There is nothing that will take us beyond the boundaries of our knowledge. We can only let ourselves be taken into the trackless ... [gap in shorthand notes] sustained by unceasing hope in a sweet, mystic semi-asleep state, on the wings of our imagination,'26It has not so far been possible to identify the book. and so on.

So what the gentleman is saying is that things have to be tangible; then we have science. The rest is a figment of the imagination. Everyone can pretend this to himself and have others pretend it for him; it is fantasy, for we simply cannot know anything about it. And if people take comfort in all kinds of supersensible things, well, we need not deprive them of this.

It is really terrible to see the confusion that has arisen about this. Now, however, I'll show you how these gentlemen have literally forgotten how to think with this science of theirs. I'll demonstrate this to you by referring to another passage in the same book. For what does this gentleman—who says everything we cannot touch is a matter of belief—do? He says it is nonsense, scientifically speaking, to think of an eternal I living in the human being, for the I is merely the sum total of everything else we have in us. We are in the habit of taking everything we think and feel, from beginning to end, together and consider it a single whole. And having made it a whole we call it our ‘I’. That is what the gentleman says.

He then wants to illustrate this. He wants to show that we do truly bring everything we experience in life together and call it our ‘I’. For in that case ‘I’ is just a word, as we are simply putting it all together. He then offers an analogy. He compares everything the human being experiences in life with an army, a company of soldiers. And so everything I have known in my youth, as a child—the way I played, the feelings I had when playing—is one group of soldiers; the things I came across a bit later are another group of soldiers, and so on. I then gather up everything there has been to this day, just as soldiers are brought together in a company, and call it ‘I’. That is what he says. He therefore compares all the individual inner experiences we have had with a company of soldiers, and makes them a group the way we put things in groups, not saying Miller and Tennant and so on, but 'No. 12 company' and so on. He thus gathers up all the inner experiences of the I in a company of soldiers. And he goes on to say: 'On the other hand there is something else to be said about the I, for it must also be taken into account that from the time of life when conscious awareness has to some extent developed, one always feels oneself to be the same “I”, the same person.' What he is saying, therefore, is that we must finally get people out of the habit of feeling themselves to be an I and get them used to the idea that this is no more than as if one is gathering together a company of soldiers.

‘Seen from our point of view, this should not really be particularly surprising. In the first place, we must be clear in our minds, if we want to consider this more closely, about the way we should really consider the individual person in relation to the outside world.' So he first of all tells us nicely that we should form an idea. And his answer is: 'It is the result of all kinds of individual ideas, and above all ideas that bring the direct interactions between the organism and the outside world together in a more or less compact whole. In our view, the idea of the I is no more than an abstract idea of the highest order, built on the sum of all the thinking, feeling and will a person has, and more than anything all ideas concerning interrelationships between one's own body and the outside world. The term brings all this together, just as the term "plant world" encompasses the infinite sum of all plants. The word “I”’—this is where it gets interesting—‘is the representative of all these ideas, more or less the way the leader of an army represents all the individual soldiers. Just as we can say of the actions of an army leader that in the minds of individual soldiers and units within the army he provides the bedrock, more or less darkly and unconsciously, exactly so do a mass of individual concrete ideas and feelings provide the basis, the bedrock, for the term “I”.’

Well now, gentlemen, just consider the way the man is thinking. It is a very learned book, we have to recognize this, at the highest level of science. The man says that we have a company of soldiers and the leader of the army. But only the soldiers are taken all together; the leader is merely their representative. And the same is said of ideas and feelings. All thoughts and feelings are taken together, with the I merely their representative.

But you see, if the I is the representative, if it is a mere word, then in the case of a company of soldiers the leader of the army must also be regarded as a mere word. Have you ever known a case where the leader of the army, the man leading a company of soldiers, is just a word, a word put together from all the individuals? Well, we might imagine that the leader of the army is not particularly bright. Sometimes the I, too, is not particularly bright. But to imagine that the leader of the army is nothing but a word—and this is the analogy he uses for the way the I relates to our ideas—simply proves that even the cleverest of people turn into blockheads when they are supposed to say anything about things that are not apparent to the senses. For as you have seen, we are able to show that when they produce an analogy it is completely without logic. There's no logic there at all.

Having produced his nice analogy, the gentleman went on to say: 'This shows that the concept “I” always depends entirely on the basic idea someone has. It can be seen most clearly as it gradually develops in a child. But every thinking adult person can also establish for himself that he feels himself to be a different I now than he did ten years ago.'

So let me ask Mr Erbsmehl or Mr Burle if you feel yourself to be a completely different I than you were ten years ago! I am sure you are able to tell if you are someone quite different now than you were ten years ago! But you come across such passages wherever you look in books today. The most ordinary facts of everyday life are turned upside down. It is of course complete nonsense for someone to say he feels himself to be a different I than he did ten years ago. But that is what those gentlemen say. But the moment you start to think about the I, if it is the same today as it was ten years ago, you no longer find, you are no longer able to say, that the I dies when the corpse dies. The question is why?

I have spoken to you, gentlemen, about the way you cut your nails, the way your skin flakes off, and so on. All this happens over a period of seven or eight years. Today you no longer have a particle in you of the matter you had ten years ago. For as your skin flakes off, your inner part is all the time moving away from the body. You see, your body is like this. At the top it flakes off; then the next layer moves up and flakes off in turn; then the next one moves up, flakes off, and after seven or eight years it has all flaked off. Where is it? Where is the body you had ten years ago? It has gone the same way, only in a rather more complicated way, as the dead body does when it is put in the grave. The dead body becomes part of the earth. If you were to split the dead body up into particles as small as the skin flakes you are losing all the time, or the nails which you cut off, if you were to divide it up into such small particles, you would not notice either that the dead body goes to some place or other. One might blow it away. And that is how the physical body becomes part of the outside world over a period of seven or eight years.

But if you still feel yourself to be an I today, and your physical body died two or three years ago, then the I simply has nothing to do with the physical body, the way we have it there. But, you see, it does have so much to do with it that if you pick up a piece of chalk, you will say: ‘I’ve picked up a piece of chalk.’ Everybody says that. I had a school mate—I think I have told you this before—who was well on the way to becoming a proper materialist when he was about 19 or 20 years old. We used to go for walks together, and he would always say: 'It seems perfectly clear to me. We don't have an I, we only have a brain. The brain does the thinking.' And I'd always say to him: 'But look, you say I go, you even say: I am thinking. So why are you lying? To be really honest, you would have to say: My brain is thinking!' Perhaps one should not even say 'my', for 'my' refers to an I; surely there has to be an I if one says 'my'. People never say: 'My brain is thinking, my brain is walking, my brain picks up the chalk.' They wouldn't dream of it, for a human being cannot be a materialist in life. He would talk nonsense the moment he became a materialist.

But people cook up materialism in theory and do not consider that genuine science does in fact know that we no longer have the body today that we had eight or ten years ago, so that the I has remained. And you are also able to remember back to your early childhood, to your second, third, fourth, fifth year. You would not dream of saying that it is not the same I which then ran about as a little boy. But let us assume you have now reached the age of 40; going back to your thirty-third year you lost one body, back to your twenty-sixth year another, back to your nineteenth year a third, then a fourth back to your twelfth and a fifth back to your fifth year. You have lost five bodies and your I has always been the same. This I therefore continues for the whole of your life on earth.

The I is also able to do things with your body. It can all the time direct this body which it is losing. You see, when I walk, my legs, though quite old, are really only six or seven years old where their substance is concerned. But I control them with the old I that was there even when I ran about as a little boy. The I is still walking about. The I controls the body during life on earth.

Now I have told you that a child learns to walk, talk and think in the time which we are no longer able to remember. We cannot recall the times, of course, when we were not yet able to think. We learn to walk, to move about altogether, to use our bodies, to talk and to think. It is something we learn. And one has to control the body in that way. When you are crawling about on all fours as a young child you cannot make the body come upright unless you have the will. When you move your hand the I says: 'I am moving the hand'—the I with its will. And that is also what happens when the child has the will to come upright. The child learns to talk with the will. The child learns to think with the will. And so we have to ask: How come that the child learns all these things? And we discover that although the body is continually replaced in the course of life on earth, the I always remains the same; this I is still the same by the time we have learned to think, to talk and to walk. This I was already active in the body at that earlier time.

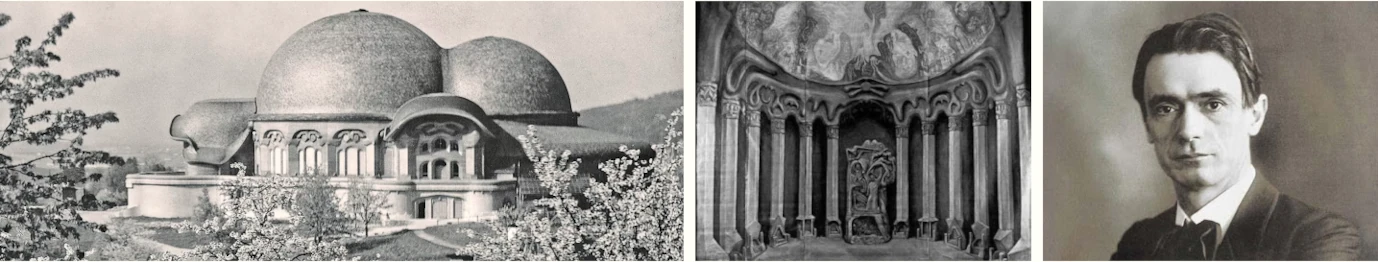

Gentlemen, I have shown you how one really gets one's body. You see, scientists think—I already explained this the last time: 'Ah well, one simply gets one's body from one's mother, one's father. Then it is all prepared, and one is already a small human being. We inherit it; the body is something we inherit.' Well, a science where it is said that we inherit the body really is not worth the powder to shoot with. For you only have to look at a bone—here you'll need to remember some of the things I told you before—if you look at a thigh bone, for example, you find it a wonderful sight. Such a thigh bone has a whole scaffolding structure. The scaffolding in the Goetheanum was nothing compared to the beautiful scaffolding one can see in the whole of this thigh bone if one looks at it under a microscope—a marvellous structure, handsomely built [Fig. 19].

If you cut off the tip of your nose—it only needs to be a very little piece, of course, for it would not be healthy to cut off too much, but one could cut off just so much that it does no harm. Looking at it under the microscope you again see a marvellous structure, most handsomely built. Yes, gentlemen, you have no idea how beautiful the tiniest part from the tip of your nose really is! Admirably well designed. And that is how it is with every part of the human body. It is handsomely built, perfectly arranged. The best of all sculptors could not do better.

There is only one part in the human organism where everything must be destroyed, so that there is nothing but matter—I referred to this the last time. This happens in the egg from which the human being develops. And with fertilization we have the last act; form or design is removed from matter.

We are therefore able to say that the bone is beautiful; every single thing is beautiful. The tip of the nose is not as beautiful as the bone but it is still most handsome. But the egg, from which the human being will later arise, contains nothing but matter in complete chaos, for in there everything is shattered. It is all atom, and there is no form in there at all. Why?

A human soul cannot simply enter into a bone. Superstitious people sometimes think there is a little devil somewhere in their bones or limbs. Well, figuratively speaking that may sometimes be true, but a human being certainly cannot enter into such a bone. Nor can a human being enter into the tip of your nose. I did know a lady once who insisted she had the holy spirit in her left index finger, and she'd always consult it if she wanted to know anything. She'd do so if she thought of going for a walk, and so on. But that's nonsense, of course, superstition. What we have to say is that no human being, no human soul, no human spirit can enter directly into such a well-designed bone, nor into the tip of one's nose. The thing is like this. The human soul and spirit, the I itself, can only enter into the egg because there matter is nothing but dust, world dust. And what happens is that the soul then works on that world dust with the powers it has brought with it from the world of the spirit.

If people believe that a person simply comes from a father and a mother by means of heredity, then one has to assume that there is a tiny human being there. But that goes against scientific knowledge. Scientific knowledge tells us that the protein in the egg is reduced to dust. And the soul, coming from the world of the spirit, from a world that is beyond sensory perception, actually builds the human body out of this protein that has been reduced to dust.

Now you may ask why a child looks like his father or his mother. Well, gentlemen, that is because the child always goes on imitating. Someone who says: 'He is the spitting image of his father' could also put it differently. You see—let us wait a while with the child—let us say we have a child who looks very much like his father or his mother, though in fact it is not all that marked. Children grow much more similar later on than they are when they are very small. But of course such things are of no interest to the learned gentlemen. But let us wait a while and not form an opinion when the child is only one or two weeks old, or a month; let us wait until the child is three or four years old. He will have started to talk then. Someone comes along and says: 'Amazing. The father is German, the child is also starting to talk German; he must have got it from his father; he's inherited it from his father, for his father is German. This is quite amazing! Since the child has come from the fertilized egg, the language must have been there already in the egg. It is only surprising that the child was not able to talk when he came from the egg, from his mother's womb.' But I think you'll agree that the child did not inherit his speech at all, he acquired it by imitating others. His speech is similar to that of his father and mother. But no one would dream of saying the child inherited his speech.

In the same way the face is similar. But why is the face similar? Because the soul, when it lets itself be born by a mother or begotten by a father, who is Mr Miller, makes the face similar to that of the father or mother, just as the child will later make his speech like that of his father and mother. This is something you have to consider. The child develops the sounds, the words of his language by making himself similar to his parents or the people who bring him up. But earlier than that the soul is unconsciously working like a sculptor on the face, or the gait, and so on. And the similarity arises because the child has been born into the family and makes himself resemble them when he does not yet have conscious awareness. This happens in the same way as the similar way of talking develops.

You see, gentlemen, in this way we discover that the human being does indeed come from the world of the spirit, the world not perceptible to the senses, and builds his own body with all its similarities. Just look at an infant. The infant is born. Sometimes it is not easy to distinguish children from little animals when they are newly born, though their mothers will, of course, find them most beautiful. You see, people are little animals when they are born—compared to later on, of course. They are really quite unattractive, those infants. But the soul element is gradually working things out in there, making it all similar, more and more similar, to a human being, until the moment comes when the infant learns to walk, which means he finds his balance on earth, as I told you the last time. Then the child learns to talk. He learns to use the organs in his chest, for these organs are located in the chest. Then he learns to think, meaning he learns to use the organs in his head. So let us consider this. The child learns to walk, which is to keep his balance and to move. What does he learn when he learns to walk? He learns to use his limbs as he walks. But we cannot use our limbs without at the same time also using our metabolism. The metabolism is connected with the limbs. Walking, keeping one's balance, moving has to do with the metabolism and the limbs.

Then the child learns to talk. What does this mean? Talking has to do with the organs in the chest, with breathing. The child has been able to breathe even as a young infant. But to connect words with the air he pushes out, that is something the child learns with the organs in his chest. Keeping one's balance is therefore connected with the limbs, talking with the chest, and thinking with the head, the nerves.

And now we have three elements that make up the human being. Just consider this, three aspects. In the first place we have our limbs and metabolism, in the second place a chest, and thirdly our thinking, the head. We have three aspects of the human being.

1. walking, keeping balance, moving—limbs, metabolism

2. talking—chest

3. thinking—head (nerves)

Now let us take a look at the child. It is like this with a child. When he is born he differs from an adult not only in the way he looks—the cheeks are different, the whole form; the forehead looks different; I think you'll agree the child looks different. Inside, however, he is even more different. The brain mass is more like a brain mush in the infant. And up to the seventh year, up to the time when the child gets his second teeth, this mush, this brain mush, is made into something truly marvellous. From the seventh year onwards the human brain is quite marvellously structured. The soul, the spirit has done this inside; the element of soul and spirit has done this inside.

But you see, gentlemen, we would be unable to shape and develop this brain in such a marvellous way up to our seventh year if we were not all the time in touch with the world. If you have a child who is born blind, for instance, you'll immediately see that the nerves of vision and with them a whole part of the brain remain a kind of mush. This is not beautifully developed. When someone is born deaf, the nerves of hearing, nerves that come from the ear and cross here [drawing on the board], after which they go over there, remain a piece of brain mush along this way. It is therefore only because we have the senses that we are able to develop our brain properly in the first seven years of life.

But the brain does not develop anything for you that you might reach out and touch. You could of course stuff tangible materials up your nose, if you like, and into the brain—you would ruin your brain with this, but it would not lead to anything. All the matter we can reach and touch therefore does not help you to develop the brain in the first seven years. It needs the most subtle forms of matter, like the subtle matter that lives in light, for example. Ether is what is needed.

You see, this is most important. We absorb the ether through all our senses. So what is it that develops all this activity coming from the head? The activity that comes from the head and also extends to the rest of the child's organism does not come from the physical body. The physical body is not active in the marvellous development of the child's brain; it is the ether body which is active. The ether body, of which I have told you that we still have it for two or three days after we die, is at work in the child. It makes the human being develop a perfect brain and thus become a thinking human being. We are therefore able to say that the ether body is active in our thinking.

With this we have once again found the first supersensible aspect of the human being—the ether body. A child would not be able to develop his brain, he would not be able to have a human brain in him, if he were not able to work with the ether body that is all around. Later on in life we can strengthen our muscles by making them work, by physical, tangible methods. But the left parietal lobe of the brain, let us say, to take an example, cannot be strengthened by any physical or tangible means. To make the muscle stronger you could use a weight and lift it again and again, overcoming gravity. But you have to use a material, tangible thing to strengthen the muscles. Just as you have your biceps muscle here, and are able to strengthen it by lifting and lowering weights, in the same way you have here, looking at the head from the front [Fig. 20], a brain lobe. It hangs there just as the arm hangs here. You can't attach weights to it. All the same, there is simply no comparison between what happens when you develop a muscle and what goes on in this brain lobe. At first, when we come into the world, it is mushy; when we are seven years old it has been marvellously shaped and developed. Just as the muscle in your arm is strengthened by lifting and lowering the weight, which is something tangible, getting stronger because of something we are able to see, so the brain is strengthened by something that is in the ether. Man relates to the whole world around him through his physical body, and he also relates to the whole world around him through his ether body. And that is where he gets his thinking. With this, he develops the inner parts of the head in the first seven years.

You see, if there were no sunlight coming in through our eyes, the ether that is all around us would not be able to work on us. We would not be able to bring ourselves to full expression in those first seven years. A child also has basically just feelings in the first seven years. He learns to talk by imitating others. But there is feeling, the way he feels, in this imitating process. And we have to say that light cannot call forth feelings. When we learn to talk through feeling, something else is active in us. The principle that is active in speech, through which human beings are able to talk, is not just the ether body, it is the human astral body. We are therefore able to say that as a second principle we have the astral body in us for learning to talk—astral body is just a term, I could also use another word. We have the astral body which is above all active in the chest, in our breathing, and then transforms itself as we learn to talk.

You see, people always think human beings are hungry or thirsty in their physical bodies. But that is nonsense. Think of a machine driven by water. You have to give that machine water. All right, it'll run then, and if you do not give it any water it'll stop running. What does it mean when we say the machine has stopped running? It means you have to give it more water, you have to give it a drink. But the machine did not feel thirsty. The machine does not get thirsty; it will stop, but it does not get thirsty first, otherwise it would scream. It does not do so. It does not feel thirst.

So how is the situation in the human being? When a child is thirsty he does not behave like a machine. He does not simply stop. Quite the contrary, he'll start to roar most powerfully when he's thirsty. So what is the connection between being thirsty and screaming? The screaming is not based on matter, nor on the ether. The ether can give form and structure; it is therefore able to create our form. But the ether does not make us scream. If the ether were to make us scream there would be a terrible—well, not perhaps roaring, but a continual hissing in the world. For when we look at things it is the ether which together with our eye makes us see. The ether is all the time entering into the eye. And that is why we see. Yes, but when the ether comes into the eye, it does not go z-z-z-el in the eye; you know, that is not the human ether body, for it does not lisp. Just think if just from the fact that we are looking there were to be a continuous whispering in an auditorium—that would be a fine thing! The ether body does not scream, therefore, nor does it whisper. Something else is there. And that is the astral body. And when an infant is thirsty and cries, the feeling of thirst is in the astral body. And the crying lets the infant's feeling reach our ear.

But everything I have been describing to you would still not make me able to walk. For, you see, when I create my body with the ether body, coming from the head, I might be a statue for the whole of my life. My body might be created, I might roar like a lion; my roar might always be created in a process that comes from the astral body. But if I want to gain my balance as a child, if I want to use the will, therefore, so that I may walk, take hold of things, gain my balance—all things where I say 'I walk, I take, I gain my balance'—then the I is coming in as well, and this is a little different from the ether body and the astral body. And this I lives in my limbs and metabolism. When you move your limbs, that is the I. So you have three aspects of the human being, apart from the physical body. You have the ether body, the astral body and the I.

I—walking, keeping balance, moving—limbs, metabolism

astral body—talking—chest

ether body—thinking—head (nerves)

And you see, these three aspects of the body can be perceived if we first train ourselves for this. But in modern science people do not want such training. And I am now going to tell you how people behave in modern science who do not want to do this.

I am sure you've all had dreams on occasion. Whilst you are dreaming you believe it all to be reality. Sometimes you wake up in a dreadful state of fear, because you are standing on a precipice, get giddy and fall down, for example. You wake up dripping with sweat. Why? Because you thought the precipice was real. You are in bed, lying there quietly, there is absolutely no danger, but you wake up because of the danger you've been facing in the dream image. Just think, if you were to sleep all your life—that would be a nice thing for some. There are people who sleep all through life.

There was someone once who had studied Copernican theory. He was a terribly lazy chap. So one day he was lying in a roadside ditch. Another fellow came walking along and said: ‘Why are you lying there?’ ‘Because I have so much to do!’ ‘Come on, you aren't doing a thing!’ And he said: ‘I have to move with the earth's orbit around the sun, and I want to stay behind. It's too much of an effort for me, too much to do!’ You know, some people don't even want to move with the earth around the sun. But we do go along with the whole of our waking life. You see, if we were to dream all our lives, we might lie in bed in Europe, say; someone would pick up our body—perhaps with the bed, so that he won't wake us—and take it to America on a boat. It would, of course, need angels to do this, for people cannot do it that surreptitiously, but it would be possible to transport us to America. There we would dream on, and anything might be done with us; we would know nothing about ourselves. Dreaming there, we'd never know how the nose feels to the touch, how the left hand feels when taken hold of by the right. And yet, gentlemen, we'd have a whole life. If we were to dream for the whole of life, it would be something different—we might be able to fly in our dream, for example. Only the fact is that on earth we cannot fly; in our dream we fly. We would think ourselves to be quite different creatures, and so on.

But just consider, there would be a world all around us as we dreamt our way through life. And we do, of course, wake up. Let us say I wake up and I have been dreaming that during the night—let me take a promising example—I was hung by the neck or beheaded. Let us assume someone dreams he's been beheaded. It would not be as great a cause for concern for one as it would be here. One might perhaps have it happen on several occasions that one dreams one is beheaded and one would believe that this did no harm. Now you wake up—and lo and behold, you had taken a book to bed with you and that has come to lie behind your back as you turned over. So now your head is lying on the edge of the book, which is uncomfortable, and in your dreams this makes you think you have been beheaded. Once you're awake again you realize what the dream meant; after waking up you can discover where the dream has come from.

So we must first of all wake up. Waking up is what matters. For people who dreamed all their life their dream world would be their only reality. We only begin to take our dream world for a fantasy world when we wake up.

Well now, gentlemen, a person wakes up in bed of his own accord or because the world around him shakes him awake. But it needs a special effort to wake up from the life in which we are, the life where we think the only things that exist are those we can grab hold of. And how to do this, how to wake up, that is something I have described in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds.27See note 19. Just as we wake from a dream and know that the dream is a world which is brought about by the waking state, so we wake from our waking state when we gain higher insight and know that our ordinary world comes from the things we perceive in that higher waking state. It is something one knows.

In future, therefore, science must develop so that we do not just dream on in the world, always only trying to see how one may do things in the laboratory, in the physics cabinet. It must show people how to wake up. Then people will no longer say: 'Man is only a physical, material body' but 'Man consists of physical matter, of the ether body, astral body and I.' And of these one would then be able to say: 'We now know the part of the dead body that is a waking-up part, even when we die.' For the ether body first had to come to the physical body and shape and create the physical body using the head. The astral body had to come, first had to dig itself in a little in the chest, and then the person learned to talk. And the I had to come to the physical body and get it in balance in the outside world. The body then learned to move its limbs and adapt its metabolism to the movements. Man thus brings his ether body, his astral body and his I from the world of the spirit, and the chaotic matter which has been reduced to dust he shapes for himself, using the ether body, astral body and I. And these things, which he brings with him into the world, he will take with him again after death. I have already given you some indication of how that goes. So the situation is that if one really takes up this higher science, this waking-up science, one is able to speak just as well about life after death and before life on earth as one is able to speak about this life on earth. This is something we'll do the next time. Then the question as to what the human being is like when he has no body, which is before fertilization, will have been fully answered.

The next talk will be at 9 o'clock on Monday. The subject is a bit difficult at the moment, but that does not matter. The reason for it being difficult is merely that people are never prepared for these things when they are young. If they were prepared they would not find it so difficult. Today, I would say, people have to make great efforts to learn the things at a later stage for which no preparation was given when they were young. But when you see that people actually go so far as to say, 'The leader of the army is only the sum total of a company of soldiers,' you will also see that modern science certainly needs to be improved. And this, then, is something which really enables us to understand the things that are not perceptible to the senses.