From Limestone to Lucifer

GA 349

III. Dante's view of the world and the dawning of the modern scientific age. Copernicus, Lavoisier

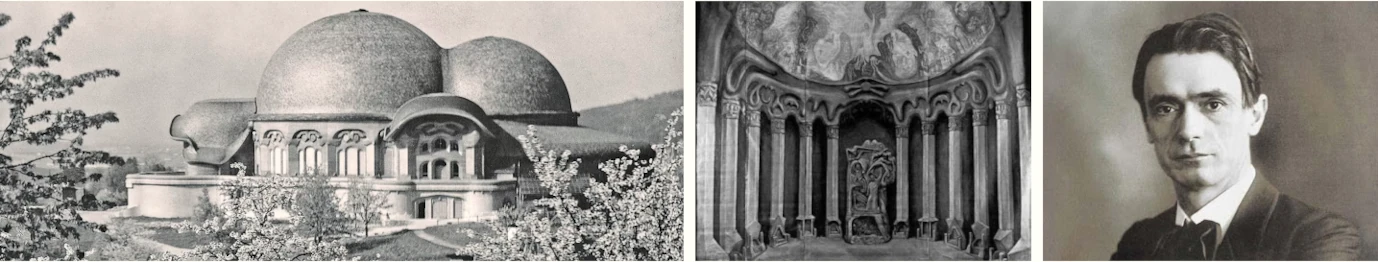

14 March 1923, Dornach

I have been given a question about the colours and asked to say some more about them.

First of all let me consider the question that was asked before that. It concerns the way Dante15Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). saw the world. The gentleman has been reading Dante. And when one reads Dante, this medieval writer, one finds that his picture of the world was very different from our own.

Let me ask you to consider the following. People think—I have told you this a number of times—that only the things people know today really make sense. And when they hear of the different ways in which people thought in earlier times they think: 'Ah well, that was in the past.' And so one had to wait until one was able to learn things about the world that made sense.

You see, the things people learn at school today, things about the world that become second nature to them, have really only been like this since Copernicus16Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543), canon of Frauenburg Cathedral, founder of modern astronomy. first thought it up. Following this sixteenth-century idea, people thought the sun was at the centre of our whole planetary system. The heavenly bodies orbiting around the earth are first of all Mercury, then Venus, then the earth [Fig. 11]. The moon orbits around the earth. Then follows Mars, orbiting the sun. Then there are a large number of planets which relative to cosmic space are absolutely tiny and are called planetoids, -oid meaning 'like' planets. Then comes Jupiter, and then Saturn. And then still Uranus and Neptune—I don't need to draw them. That is how people see it today, how it is taught at school—that the sun is standing still at the centre. The lines followed by the planets are really a bit elongated. But this does not matter for us today. People think, therefore, that Mercury orbits the sun, then Venus does, and then the earth. As you know, the earth takes a year to move around the sun, 365 days, 6 hours and so on. Saturn goes all the way round once in 30 years, which is much slower than the earth. Jupiter for example takes 12 years, which is also slower than the earth. Mercury moves fairly quickly. The nearer the sun the planets are, therefore, the faster they move.

As you know, that is believed to be the correct view today, and it is taught in the schools. But we only need to go back as far as the fourteenth century, about the year 1300, to find that an extraordinarily great mind like Dante had quite a different idea. So that was a few centuries earlier than Copernicus. And the greatest human being, Dante, the greatest in mind, then had quite a different idea.

We won't decide right away if the one idea or the other is the right one. Let us now look at the way Dante, one of the most important thinkers of his time, saw the matter at that time—it's 1900 now, then it was 1300—so it was only 600 years ago. Let us not think the one is right and the other wrong, but try and enter into the way Dante saw things. He thought [Fig. 12] that the earth was at the centre of the universe. And this earth is not only such that the moon, for instance, reflects the light it receives from the sun onto the earth, but the earth is not only orbited but is wholly enveloped by the moon sphere. Dante therefore saw the moon as something much bigger than the earth. He saw it as a very subtle, very fine body that is much larger than the earth. It is subtle, therefore, but much bigger. And the object we see is just a little bit of the moon, the solid bit. And this solid bit orbits the earth. Can you visualize this? For Dante the idea was that the earth was inside the moon, and the bit we see of the moon is only a tiny, solid part of it. That moves in orbit. But in reality we are all of us inside the powers of the moon. I have drawn this in red.

And the way Dante saw things was like this: if the earth were not within those powers of the moon, human beings might one day come to the earth by some kind of miracle, but they would not be able to procreate. The reproductive powers are in the sphere I have drawn in red. They also stream through the human being, and make human beings capable of reproducing themselves. Dante therefore imagined the earth to be a small, solid body; the moon he thought was a subtle body—much more subtle than air—a large subtle body, with the earth inside it like a kernel. You can imagine the earth like a plum stone in the soft fruit pulp of the plum. And out there is the solid bit; this moves in orbit. But this [Fig. 12, moon sphere] is also always present, and it is because of this that human beings are able to reproduce themselves, and animals, too, are able to reproduce themselves.

He also considered the following. The earth is not only inside the moon powers but it is also inside other powers—I'll make them yellow here—and they penetrate all the rest of it. So you have the moon powers in there, and earth and moon are both inside this yellow sphere. And again we have a solid part. This solid part is the planet Mercury which orbits out there. And if human beings did not have the powers of Mercury in them all the time they would not be able to digest. Dante therefore thought the powers of the moon made reproduction possible, the powers of Mercury—and we are also always inside them, only they are more subtle than the moon powers—make it possible for us to digest our food, and for animals to digest their food.

Otherwise we would just have a chemical laboratory in our bodies, he thought. It is due to the powers of Mercury that things go differently in our bodies than they do in a chemical laboratory where substances are merely mixed together and then separated again. This is due to the powers of Mercury. Mercury is thus larger than the earth and larger than the moon.

And now everything is inside another sphere, as Dante called it, which is even bigger. So we are also within the powers that come from this planet, from Venus. We are thus inside all those powers, and they enter into us. Because we have Venus forces in us we are able not only to digest but also to take anything we have digested into the blood. Venus powers live in our blood. Everything that has to do with the blood in us comes from the powers of Venus. That is how Dante saw it. And these Venus powers create any feelings of love human beings have in their blood—hence the name Venus.

The next sphere is one we are also inside, and here the sun moves around us as a solid part of it. We are thus completely within the sun. For Dante in the year 1300, the sun was not just the body that rises and goes down; his sun was present everywhere. Standing here I am inside the sun. For the body that rises and sets, and moves along over there is only part of the sun. That is how he saw it. And the powers of the sun are above all active in the human heart.

So there you have it. Moon, human and also animal reproduction; Mercury, human digestion; Venus, development of human blood; sun, human heart.

And Dante then thought that all of this was inside the vast Mars sphere. There is Mars. And just as the sun is connected with the human heart, so Mars—and we are also inside this—is connected with everything to do with speech and everything we have by way of breathing organs. That is in Mars. Mars, then—breathing organs. And there is more of it. The next sphere is the Jupiter sphere. We are also inside the Jupiter powers. Jupiter is, of course, very important; it has to do with everything that is our brain, really our sense organs, our brain with the sense organs. Jupiter is thus connected with the sense organs. And then comes the outermost planet, which is Saturn. Everything is again inside this. And Saturn has to do with our organ of thinking.

Moon—human reproduction

Mercury—human digestion

Venus—human blood development

Sun—human heart

Mars—breathing organs

Jupiter—sense organs

Saturn—thinking organs

So you see that this man Dante, who was only 600 years before us, saw the whole universe in a different way. He believed Saturn, for instance, to be the biggest of the planets in which we are. And those Saturn powers create our thinking organs, they make it possible for us to think.

Now beyond all this, but again in such a way that we are inside it, is the firmament of fixed stars. Those then are the fixed stars, and above all the zodiac [Fig. 12]. And even greater is that which sets it all in motion, the prime mover. This is not only up there, however, but is also the prime mover everywhere here. And beyond it lies eternal rest, a calm that also exists everywhere else. That is how Dante saw it.

Well now, someone may come today and say. 'That is the way it is; people saw everything imperfectly then. But today we have finally reached the point where we know how things are.' Sure, that is what one might say. But Dante was not exactly stupid, and he also saw the things people see today. So he was not exactly stupid. And the others, from whom he took his ideas, people who all held that belief at the time, were not exactly silly people either. It is just that they had different ideas about it. And the question is, how has it happened in the history of the world that people thought differently about the whole nature of the universe in earlier days, and then suddenly turned everything upside down in the sixteenth century and developed a completely different idea of the world?

This is, of course, a very important question, gentlemen. And you will not get anywhere by saying, oh well, those earlier ideas were childish. For those people did see things very differently from the way people see them today. This is something we must understand. They saw something very different. Modern people are able to think so terribly well. And those earlier people were not able to think as well as people do today. Thinking is really something that has only developed gradually. The people of those earlier times had a terrible fear of Saturn, which is connected with the organ of thinking. Saturn, they thought, ruins the human being. It is not good to think too much. Saturn was always considered to be a dark planet. And they thought the powers that came from Saturn would make people quite melancholic if they became too powerful in them. They would then think all the time and grow melancholic. So they were not too keen on the Saturn powers, and tended to visualize things more in images. They did not calculate so much. Today we calculate everything. Copernicus' image of the world has all been calculated. Those earlier people did not make calculations. But they knew something else, something modern people do not know. They knew that powers were active everywhere in the world, wherever you looked. But these powers, which are also in the human being, are not in the world we see with our eyes; they are in the invisible realm.

And so Dante said to himself: 'There is a visible world, and an invisible world. The visible world—well, it is the one we see. Looking out there at night we see the stars, the moon, Venus, and so on. That is the visible world. But there is also the invisible world.' And the invisible world consists in those spheres, as they called them in the old days. And they distinguished the world one sees with one's eyes, and called it the physical world. That was the physical world. And they distinguished the world one does not see with one's eyes. That is the world Dante was thinking of, and it was called the etheric world. That was the etheric world, the world which consists of such subtle matter that one is always looking right through it.

Well now, gentlemen, I do not know if you have come across this, but I have known people who insisted that there is no such thing as air, for one cannot see it. They would say: 'Well, if I go from A to B, there is nothing there; I am not walking through anything there.' You know that there is air there, and I walk through it. But, as I said, I have known people who did not have the education which modern people have, and they did not believe that there is any air; they would say: 'There's nothing there.' Dante knew that there is also not just air, but moon, Venus, and so on. It is just the same. You say: 'I am moving through air.' Dante would say: 'I am walking through the moon, I am walking through Venus, I am walking through Mars.' That is the whole difference. And all the things one does not see in the ordinary way, and which one is also unable to detect with the usual physical and chemical apparatus—all this was called the etheric world. Dante was therefore speaking of a very different world, an etheric world. And why was it that Dante saw the world differently 600 years ago? It was because he wrote of something else, he wrote of the invisible realm, of the etheric world. And all that Copernicus said was: 'Let us forget the etheric world and describe the physical world. For that is progress.' So you should not think that Dante was a clown, for he was simply writing about the etheric and not the physical world. The physical world was not particularly important to him. He wrote about the etheric world.

Now you see, the whole only changed to any major extent at the end of the eighteenth century. Up to the end of the eighteenth century people always still knew something about this etheric world. In the nineteenth century they no longer knew of it. We are discovering it again through anthroposophy. In the nineteenth century people knew nothing of this etheric world.

Concerning your other question—

If we go back to the eighteenth century, we find people did the following, for example. They would say: 'Here we have a candle, with its wick. And the candle is burning.' Now you know that when a candle burns it is bluish at the centre, and yellowish around the edges [Fig. 13]. You can explain this very nicely because of the things we have said about the colours. You see, at the centre it is dark, and here it is light [around the outer edge]. And the result is that you see darkness through light. And you know, for I told you this the other day, when we see darkness through light it looks blue. The inside of a candle flame therefore looks blue, because we see darkness through light. I just wanted to draw your attention to this, so that you may see that the ideas and views about colour I have told you the last time apply in every case.

Now you know that when a candle burns it gets less and less. Up above is the flame, and the candle material which melts here [on the candle] goes into the flame. In the end the candle has gone. The material of the candle has spread out into the air.

Now imagine someone who lived, let us say, in 1750, which is not quite 200 years ago. He would say: 'Right, if the candle burns there and it all goes into the air, something of the candle goes into open space. Nothing is left of it in the end. And so the whole candle must go out into open space.' He would also say: 'It consists of some subtle material, fire stuff. This fine fire stuff unites with the flame and goes off in all directions. So in 1750 someone would still say: 'Inside the wax is some stuff that has merely been squashed together, made denser. When the flame makes it into fine matter it goes out into open space.' The stuff was called 'phlogiston' in those days. Something therefore comes away from the candle. The fire stuff, the phlogiston, comes away from the candle.

Then someone else came at the end of the eighteenth century and said: 'No, I do not really believe that there is a phlogiston that goes off into the world. I don't believe it!' What did he do? He did the following. He also burned the whole thing, but he did it in such a way that he captured everything that evolved. He burned it in an enclosed space, so that he was able to capture anything that might evolve. And then he weighed it. And he found that the whole did not grow less in weight. So he had first weighed the whole candle, and then the little bit that was left when the candle had burned down to there [drawing]; and he captured anything that developed in the burning process, weighed it and found that it was a little bit heavier than before. When something burns, he said, whatever evolves does not grow lighter but heavier.

And the person who did this was Lavoisier.17Lavoisier, Antoine Laurent (1743-94), French chemist. Why was it that he took such a different view? It was because he was using scales, because he weighed everything. And he then said: 'If it is heavier, it cannot be that something went away, but something must have been added. And that is oxygen.' Before that, people had thought phlogiston was flying away, and afterwards people thought that if something burns, oxygen comes in, and in combustion one does not have phlogiston dispersing, but oxygen actually being drawn in. This has come about because Lavoisier was the first to weigh these things. Before that, people did not weigh them.

You see, gentlemen, it is as plain as can be what really happened there. By the end of the eighteenth century people no longer believed in anything that could not be weighed. Phlogiston was of course something they could not weigh. Phlogiston did go off. Oxygen did come in. But the oxygen could be weighed when it combined with other matter. Phlogiston could not be captured. Why? Well all the things Copernicus observed when he studied Mars and Jupiter are things that are heavy when you weigh them. The body Copernicus called Mars would weigh something if you put it on some really big scales. So would the body he called Jupiter. He only looked at the bodies that had weight.

Dante did not just look at bodies that had weight but rather at things that had the opposite of weight, things that forever want to go out into cosmic space. And phlogiston simply belongs to the things Dante observed, whilst oxygen belongs to the things Copernicus observed. Phlogiston is the invisible principle that disperses, the ether. Oxygen is a substance you can weigh.

So you see how materialism came into existence. This is something that may become extraordinarily important for you. Materialism arose because people began to believe only in the things that could be weighed. The things Dante still saw could not be weighed. If you walk about on this earth, we can weigh you as well. You have weight, and if you consider the human being to be only the part that has weight, all you have is the earthly human being. But remember, this earthly human being will be a corpse one day. Everything that has weight, that can be treated with scales, will be a corpse. Then the corpse lies there. You will still be able to live in the part that does not have weight, the part that exists around this earth and which materialists say does not exist. Dante still spoke of it and we'll have to speak of it again, of the fact that it exists. We are thus able to say: when a human being lays aside his outer, heavy body, which can be weighed, he remains at first in the ether body.

And now I am going to tell you what is actually there in the ether body. You see, if there is a chair here I can see that chair. I have a picture inside me of this chair. But I don't see it any more when I turn round. But the picture of it is still inside me, still a real picture. It is the memory picture.

Now think of memory pictures. Think of some event you saw and heard quite a long time ago. Say you were in some place, saw cheerful people dancing in the market square, and so on. I could equally well mention some other thing. You have retained that picture. The event you have as a picture no longer exists, gentlemen, and above all it is not among the things one can weigh. It can only be visualized in you. You may go about today and, if you have a lively imagination, have a clear idea of how it all went, even the colours worn by those who were leaping about. You have the whole picture before your mind's eye. But you would never think for a moment that one can weigh the things you saw once long ago. This thing here you can put on the scales. Individual people have weight. But the memory picture you have in you cannot be put on any scales. That is not possible. It has remained with you, though physically the matter no longer exists. How does it come to be inside you, this memory picture? It is in you etherically. No longer physically, but etherically.

Now imagine you have gone for a swim, and because of some mishap you are close to drowning; but you are saved. People who have almost died from drowning and have been saved have generally told others of a most interesting memory picture they had. It is also possible to have this memory picture if one is not about to drown but trains oneself in the science of the spirit, in anthroposophy. The people who were close to drowning had a review of their whole life, right back to their childhood. Everything rises before the mind's eye. Suddenly there is this memory picture. Why? Well, gentlemen, because the physical body, which is now in the water, goes through a very special process. And here you have to recall something I have told you on another occasion. I told you that if you have water and a body in it, the body grows lighter in the water [Fig. 14]. It loses as much weight as a body of water of the same size.

A nice story is told of how this was discovered. The discovery that a body always grows lighter in water was made in ancient Greece. Archimedes18Archimedes (c. 287-212 bc), Greek mathematician, physicist and inventor. gave a lot of thought to these things. And one day he was having a bath. People were absolutely astonished—yes, when you took a bath in Greece, other people were able to look on—people were absolutely astonished when Archimedes suddenly leapt from his bath and shouted: 'Eureka! Eureka!' That means: 'I've got it!' People thought: what has he found in his bath? He had immersed himself in the bath, leaving just the head out. He raised a leg above the water and found that when he put his leg out of the water it grew heavier; when he put it down into the water again, it got lighter. This is what he was the first to discover in his bath. It is known as Archimedes' principle.

Every body is therefore lighter in the water. And when someone is drowning his physical body grows light, very light. The memories he has in his ether body continue, and they will all come up at this point. And you see they come up because he is no longer so heavy. When human beings die they are completely outside their physical bodies, and this means they are very light. They then live wholly in the ether sphere. After their death they thus remember everything they lived through on earth, all the way back to their childhood. The first experience we have after death is this complete memory.

We can test this memory. We can do so by taking up the training I have described in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds.19Steiner, R., Knowledge of the Higher Worlds, How is it Achieved? (GA 10), tr. D.S. Osmond, C. Davy, London: Rudolf Steiner Press 1976. Also available as How to Know Higher Worlds. A Modern Path of Initiation, tr. C. Bamford, Hudson: Anthroposophic Press 1994. We can then always have this complete memory. We know that the soul grows independent of the body. It then first of all has this memory, for it does not, to begin with, live in the matter we are able to lay aside but rather in something that wants to go out into the whole wide world. That is the first state after death. You remember. The second state is something I'd like to talk about the next time. Now let me speak of something that will prepare us. For the question that has been put concerns a very serious matter.

If you consider that Dante had ideas about the world which people call childish today, then the other ideas he had will be considered really childish by people today. For if someone is standing there on the earth [Fig. 14], Dante would think: here in the earth, in the other direction—that is if one goes through there—one would find hell, as he saw it, in there in the earth. His idea therefore was: 'Out there everywhere is the ether of heaven. But if I were to drill down into the earth, then hell will be there on the other side. Before I emerge from the earth, hell will be there.'

Now it is terribly easy for people today to call such a thing childish. You'd only have to say: 'Yes, but if Dante had stood here, and not here, he could have made his hole here and then hell would have been there (on the other side).' Well, modern people can say that because modern people know that there are also people living on the other side. It is therefore easy to say Dante was just ignorant, and was quite unable to see that there are people all around the world, so that hell might just as well be here or over there. For if someone were to stand here, he would get heaven from this side, and hell would then be on the other side for him.

You see, gentlemen, it's like this. For the physical world it can only be like this: if heaven were there, hell could only be here. For the physical world that is the only possible way. If a chair is in a particular place, it can only be in that place. There's no other place where it could be at the same time.

But Dante did not see it like that. He was not thinking of the physical world at all. He was thinking of forces. And he said: 'Yes, if someone stands there, and if he moves in an upward direction with his own ether body, he'll get lighter and lighter. He'll overcome gravity more and more. But if he goes down into the earth he must make more and more of an effort, and the effort that is needed will be greatest when he's reached the other end. There everything will exert pressure on him. And gravity will be greatest.' This is not because there is any kind of particular hell there, but because he's gone through all that in order to reach that place [Fig. 14].

And if that is the way Dante saw it, then he could also stand there [at the other end]. Going out from there he'd get lighter and lighter, getting more and more into the ether. But if he moves into the earth there, he has to go through that [getting heavier]. And the condition, the experience will come in the place I have marked in green; earlier it would have been where I have put yellow. So that is the point of it. It does not mean that hell is exactly in this place. Dante wanted to say: 'If someone has to work his way through the earth with his ether body, the heaviness and hardship will be so great that wherever he ends up, be it at the top or at the bottom, he will have an experience that is hell to him.' It has only been very recently that people have imagined hell to be in a particular place. Dante thought of the experience you have when you have to work your way through the earth as an ether human being.

Anyone saying that Dante was ignorant only shows himself to be ignorant in thinking that Dante imagined hell to be on the other side of the earth. What Dante actually thought was: 'Wherever I fly away from the earth and into heaven I will get lighter in soul; if I enter into the earth somewhere, then whichever place I get to at the other end—hellish.'

The whole way of thinking has changed. And only if you are able to take some heed of the completely different way of thinking people had before, you will also be able to understand the things I am going to say the next time we meet in answer to the question: What remains of the earthly human being when he has gone through the gate of death?

It has been a bit harder than usual today. But you have to consider that this is due to the nature of the question that has been asked. I hope things will now be a little bit clearer. We'll continue on Saturday when we'll look at the human being as he goes through death and what then becomes of him.