From Crystals to Crocodiles

GA 347

IV. The human being as body, soul, and spirit. Brain and thinking. The liver as organ of perception

9 September 1922, Dornach

Well gentlemen, as quite a bit of time has elapsed since my last lecture, I would like to review what we talked about last time. We discussed sleeping and waking and the connection between them. I also mentioned that we have very small organisms or cells in our brains, and I made a drawing of them for you. These cells consist of a body made of protein that extends into a star shape [see below]. These extensions are of varying lengths. Close to the first organism we find another one with its arms and so forth. These extensions or arms intertwine and form a mesh. This is why we find that the brain is actually a mesh containing these tiny dots when we look at it through a strong microscope.

The most striking thing about these brain cells is that they are almost dead. Small creatures such as these brain cells would move if they were fully alive. I also spoke about another type of cell, the white blood corpuscles. They look like small creatures, and that is what they are. And like small creatures, they float around and feed. If there is anything in the blood that they can absorb, they extend their feelers and suck it in. They float and move through our bodies, and thus there are organisms floating around in our blood that are half dead and half alive.

When we are awake, the brain cells are really just about lifeless. And it is only because of this that we are able to think. If the brain cells were more alive, we would not be able to think. We can see that this is so when we consider that the brain cells are more alive when we are sleeping. It is precisely when we are not thinking but sleeping that they begin to live. They do not move around because they are too close to each other, too much crowded together. If this were not so and they had begun to move, we would not wake up at all.

When we examine the brain cells of a person who had lost his mental faculties and then died, we find that they had begun to live and to proliferate. They are softer than those in normal people. This is why in the case of mental deterioration we often speak of 'a softening of the brain' and that term is not such a bad one.

When we study living human beings objectively, without prejudice, we must admit that the life in our body cannot give rise to our thinking. On the contrary, this physiological life must actually die in the brain to enable us to think. That's the way it is. If our scientists were to proceed in the right way, they could not possibly be materialists. Based on the physical constitution of human beings they would realize that mental and spiritual activities are most pronounced precisely when the physiological processes fade away, as they do in the brain. The existence of soul and spirit can thus be proved in a strictly scientific way.

At night, when we sleep, our brain cells are more active, and that is why we cannot think then. When we are awake the white blood corpuscles begin to be active. This is the difference between sleeping and waking. In other words, when we are awake, when our brain cells are paralysed and nearly dead, then we can think. When we sleep we cannot think, because our brain cells begin to come to life, while our white blood corpuscles approach a lifeless condition. As far as our body is concerned, we actually need to have something of death in us in order to be able to think and to have a soul life.

You see, gentlemen, it is not surprising that modern science does not discover such things, because it developed in a particular way. When you visit the university of Oxford, as I was able to do recently when I gave a series of lectures at that famous English university, you will be struck by the fact that the university of Oxford is quite different from those in Switzerland, Austria or Germany. Oxford University still has something medieval about it; it has a clearly medieval character. For example, the graduating Ph.D. candidates wear a gown and a mortarboard. Each university has its own style for these items. You can distinguish an Oxford graduate from a Cambridge one, because their gowns and mortarboards are different. Scholars there must wear these things at certain formal occasions so that everybody knows which university they attended. This is because in England many medieval customs have been preserved. For example, judges must wear a wig when presiding in court. Many medieval customs have survived in England and are still a part of people's lives. This is not the case on the Continent, for instance in Switzerland, Austria and Germany. Here students do not wear a gown when they graduate and judges no longer wear wigs.

Visitors from the Continent find these things funny and think that the British people are still living in the Middle Ages. These graduating scholars walk in the streets wearing their gowns and mortarboards. Yet there is more to it than meets the eye. You see science is still pursued there as it was in the Middle Ages. Compared to other, more modern universities that have abolished the old ways, the British universities are very nice—mind you, I don't want to argue for a return to gowns, but there is something very nice, something whole and complete about universities such as the one in Oxford.

They have preserved the Middle Ages in all their forms, and this gives a sense of completeness. For in the Middle Ages students at universities were allowed to explore anything they wanted except for the realm of religion. This is something you can sense even today in Oxford. If you were to talk about the supersensible world, people there would treat you with extreme reserve.

Well as long as they did not go into religious matters, medieval scientists had complete freedom, something we have lost. At our universities you have to be a materialist nowadays. If you are not, people treat you like a heretic; and if it were acceptable still, they would even burn you at the stake. You can see very clearly how people are treated who try to introduce something new into any of the scientific disciplines. To all appearances the wigs of formality have disappeared, but they continue to dominate people's attitudes here.

The sciences that developed on the Continent have kept many formal habits of the past and have become materialistic because they never dealt with spiritual matters. As I said, medieval scientists were not supposed to work with questions of the spirit, because this field was left to religion to explore. Nowadays people continue this division. They deal merely with the physical body and therefore do not learn anything about the spiritual nature of the human being. It is due only to the negligence of science that what is certainly there is not really studied.

I'd like to give you an example so that you see that anyone nowadays engaged in true science can indeed state scientifically that a soul or spirit enters the foetus in the mother's womb and leaves the human body again at the moment of death. We can now prove this scientifically, provided we really know our science and use it objectively. But what does modern science do in specific instances?

Let us say, for instance, that a person of 50 has a liver disease and dies because of it. Then an autopsy will be performed, the belly will be opened, and the liver will be examined. The pathologists may find that the inside of the organ has hardened a bit, and they will try to find out how this happened. At most, they will wonder what this person had been eating, based on the assumption that the liver may have hardened because of an inadequate diet. But nature is not that easy to understand. It is not enough to examine person's liver and then to assume we found the reason for his illness. By merely investigating the last few years of a person's life, we cannot find out why the liver was in such a bad condition.

If you find that the liver of a 50-year-old person has hardened, the reason for that is usually—not always, but usually—that as a baby this person was fed the wrong kind of milk. Often what shows up as illness at the age of 50 was caused in very early childhood.

Why is this so? You see, if you really examine the liver and know its significance, you will realize first of all that in a very young child this organ is fully intact and actually still developing. Now the liver is quite different from all our other organs; it is unique. You can see this even from the outside. If you take any other organ, for example, the heart or the lung, you can see that it is an integrated part of the body. Let us think, for instance, of the right lung. You can see that arteries go in here and that veins come out there. The arteries bring in the oxygen, which is absorbed by the body, and the veins carry used blood; they contain carbon dioxide, which must be exhaled [see drawing below].

You see, every organ—stomach, heart, and so forth—is structured in such a way that it receives arterial blood and expels venous blood. This is not so in the liver. At first everything looks the same here as in the other organs. The liver, as you know, is located below the diaphragm on the right side of the body. Initially we find that here, too, arteries carry blood in and veins move blood out. If this were indeed all there is, the liver would be an organ like all the others.

But, unlike any other organ, we also find here a large blood vessel that carries venous blood, rich in carbon dioxide, into the liver. This so-called portal vein is quite big. It branches out into many smaller vessels inside the liver, supplying it with venous blood, which has become unsuitable for any other activities and which is normally cleansed when we exhale carbon dioxide. Yes, we constantly send carbon dioxide into the liver because it requires what all the other organs must discard.

This is so because the liver is a kind of inner eye. Especially when it is still fully intact, as in a child, the liver senses not only the taste, but also the quality of the mother's milk taken in. Later on in life, it will perceive every aspect of the food we take in. The liver is an organ of perception; one could also say it is an eye or a sentient organ. The liver perceives many things.

Another organ of perception is the eye. It perceives the world around us so strongly because it is almost isolated in our head. It nestles into the orbital cavity and is thus almost completely separate from the rest of the body. Our other senses do not connect us as much with our environment as the eyes do. If you hear something, you also have an inner experience. This is why listening to music is more an inner experience than seeing something. In contrast, our eyes are arranged in such a way that they form less part of our body and belong more to the world around us.

Normally venous blood gives off carbon dioxide to the air around us and becomes oxygenated again. However, as I mentioned earlier, the blood lacking oxygen flows into the liver and thus makes this organ very different from the rest of the body, just as the eyes are. The liver, then, is another sense organ. The eyes perceive colours; the liver perceives whether the sauerkraut I eat and the milk I drink are good or bad for my body. The liver perceives these things in a very discriminating way and then secretes bile, just as our eyes secrete tears. When we are sad, we start to cry. It is not without reason that the tears come out of our eyes. Becoming sad is connected with perceiving. Similarly, the secretion of bile is connected with the perception of the liver as to whether something is good or bad for the body. The extent of bile secretion depends on how harmful something is which we have taken in.

Imagine now that a child is given unwholesome milk. This will constantly irritate the liver. The infant may still be so healthy and strong that he does not immediately succumb to jaundice due to excessive bile secretion. However there will be a constant tendency in the child to secrete bile. Thus the liver becomes ill already in early childhood. Well, human beings can cope with a lot. This sick liver may last for another 40 or 45 years. But finally, in the fiftieth year, Tiings come to a head: the liver has hardened.

Therefore it is simply not good enough to put the corpse of a 50-year-old man onto the autopsy table, open the belly, examine the organs, and then make a statement about them. In such a situation you simply cannot say anything worthwhile. Human beings are not just how they appear at any one moment; they develop over a number of decades, and that must be taken into account. And something that began long ago may express itself only 50 years later. In order to understand this, you have to know all about the person involved.

Let's assume now that you are materialists. Remember, I told you that the liver is an organ whose illnesses may have been caused at the infant stage, though they may not become noticeable or acute until the age of 50. What is going on there? Well, for simplicity's sake let's assume human beings only consist of flesh, blood, muscles, and so on. Human beings have blood vessels, arteries, nerves, and so on. All of these consist of tissue or cells, of course. But do you actually believe that the tissue in an infant's liver will still be there at the age of 50? No, it will not.

Let me explain this with a simple example: you trim your fingernails, because if you didn't they would grow as long as a hawk's talons. So you regularly cut off pieces of your own body, you can say. When you get your hair cut, you again have part of your body removed. But that is not all. You will also have noticed that tiny pieces of skin, called dandruff, come off when you have not washed your hair for a while and scratch your scalp. If you were not to wash thoroughly for some time, and if your perspiration did not wash away very small pieces of skin, your entire body would be covered with scales. Yes, we constantly lose pieces of our body at its surface.

What happens when you trim off a piece of your finger nail? The nail will grow back to that point again. It grows from the inside. This is typical of the entire human body. Tissue that was at one time innermost will reach the surface of the body after about seven years. Then it is discarded in the form of tiny flakes of skin or dandruff. Nature does this to us all the time, but we normally do not notice how these particles are discarded. The tissue in our body constantly moves from the inside to the periphery and there is sloughed off. What is deep inside your body today will have reached the surface in seven years and then will be discarded, and new tissue will have been formed inside you. Every seven years the soft tissues of the human body are renewed.

In the case of infants, this holds true even for certain bone structures. This is why we have our milk teeth only until the age of seven. Then they come out, and new teeth grow. We keep these second teeth only because we no longer have the strength to discard them, as we do our fingernails. Mind you, I know it is true that nowadays we do not tend to keep our second teeth all that long either. Especially in Switzerland, people suffer from tooth decay. This deterioration has to do with the water, particularly in our area.

This shows you that the tissue presently in your body will not be there seven years from now. You will have discarded it and replaced it with new material by that time. If it were merely a question of tissue, Mr Dollinger, who is sitting here with us, would not be the same person today he was seven years ago; for the material that made up his body then has completely disappeared by now. As far as tissue is concerned, he has become a different person. On the other hand, people addressed him by the same name seven years ago, and today he is still the same person, even though the cells within him have changed.

We can certainly see this tissue, for instance, when we dissect a corpse. But the forces that hold the tissue together, move it around, and replace it, these forces working all through us, we cannot see. They are what we call supersensible forces.

Yes, gentlemen, when an infant's liver has been damaged and finally causes serious illness at age 50, this organ inside the body has been completely renewed in the meantime. The original material that made up the liver is no longer there. Thus, the cause for the liver disorder does not lie in the tissue itself, but in the invisible forces. When the person in question was still an infant, these forces usually prevented the liver from functioning normally. Not the tissue, but the functioning, the activity of the organ, became unbalanced. If we understand this in the case of the liver, we have to conclude that, since we constantly renew tissue, we also carry something in us that is not tissue, not matter. If we fully grasp this idea, we will find it impossible to be materialists, for scientific reasons. Only people who believe that human beings are made up of the same material at age 50 as they were in infancy can be materialists. As you can see from the example I gave you, purely scientific reasons compel us to assume a spiritual basis to human life, a spiritual quality in human beings.

In other words, gentlemen, you cannot seriously believe that the original particles, long gone after 50 years, had anything to do with building and forming the liver. After all, they have been expelled from the liver. The only thing that remains of these particles now is the space they used to take up. What continuously rebuilds the liver is a force, is something supersensible.

In the same way, the entire body must be formed and constantly re-formed even before human beings can be born. The forces that work upon the liver must already be active when the foetus develops in the mother's womb. Of course, you can say that in the fallopian tubes the egg cell unites with the sperm cell, and then the human being begins to develop. Well, gentlemen, a human being can develop just as little out of this union of cells as, at age 50, a liver disease can develop out of tissue that was damaged in the first year of life. Granted, the material must be there. However, people who claim that human beings develop in the womb out of cells might just as well say that if I put down a few pieces of wood here and sit next to them for a few years they will then turn into a beautiful statue. Naturally, spiritual forces must have the material to work with; this is provided in the mother's womb. But human beings are not really formed there. It would be more accurate to say that like the wood carved by a sculptor, this material is shaped by spirit forces, thus giving rise to what continuously renews us when tissue is sloughed off or excreted. If matter were more important, we would not have to eat as much as we do. Although as children we would have to eat to grow, after having grown to adulthood at about age 20, we wouldn't have to eat anything any more if the tissue in us remained unchanged. This would be a wonderful thing for employers, because children are not allowed to work yet and adult workers would not need anything to eat! But we have to eat even when we are fully grown. This proves that what remains unchanged in human beings during their entire lifetime is not the original cell material, but the soul-spiritual forces. They must be present before conception can take place and must work on matter in us from the beginning to the end of our existence.

After birth, in early infancy, humans sleep almost continuously. In fact healthy infants should not be awake for more than one or two hours. Normally babies want to sleep most of the time. What does it mean that infants have a constant need to sleep and should do so? This means that their brain should still have a bit of life in it, and the white blood cells should not rush through the body too actively. They should still be at rest and the brain cells should be relatively active. This is why infants must sleep. Of course, they cannot think yet. As soon as they begin to think, the brain cells begin to become increasingly lifeless. As long as we are growing, the same forces that support our growth also maintain our brain in a soft, physiologically active condition. But once we stop growing or slow down, these activating forces find it ever more difficult to reach the brain even during sleep. The result is that as we get older, we learn to think better, but our brain tends more and more to approach a condition close to death. Once we have grown up, there are actually death processes going on in the brain all the time.

Of course, we are hardy creatures. For a long time after growing up, we are able to make our brains sufficiently soft at night. But there comes a time when the forces streaming up into the head can no longer supply the brain properly; then it will begin to age.

What do people actually die of? It is true, of course, that once an organ is damaged or destroyed the spirit forces can no longer work through it, just as we can no longer work with a machine once it is out of order. But apart from that, the brain becomes more and more hardened with age and more and more difficult to reconstitute to its earlier softness. During the day, the brain is constantly being worn out, because it is not the body that rejuvenates the brain, but the soul-spirit forces. But these influences are, as it were, like poison. In the waking state, the brain is being undermined by the soul-spirit forces. We must sleep in order to allow the brain to be reconstituted, rejuvenated. If the brain were unable to think, it would not be worn out but become ever stronger. For instance, the arms do not think, but work and therefore grow ever stronger. In contrast, the brain becomes weaker and weaker due to the thinking going on there. The brain does not think because of its physiological vitality but because of the death processes in it, and therefore our whole body eventually becomes unusable. The spirit is present, but the body is eventually no longer usable.

The same development can be seen in what I talked about earlier, in the liver. It functions in our body like an eye, like a sense organ. Yes, gentlemen, if the liver of a 50-year-old person has become as hardened as I described, it is ill. But there is always a slight hardening of the liver as we get older. Only in children is the liver still very soft. It consists of minute, interconnected reddish-brown lumps of tissue, the so-called liver tissue. This tissue is supple and soft in early childhood, but the older we get the harder it becomes. Just think of the eyes for a moment, where the same thing occurs. As we get older, the inside of the eye gradually hardens. In its pathological extreme, this leads to glaucoma. Similarly, excessive hardening of the liver leads to cirrhosis accompanied by abscesses and so forth.

But even if we remain healthy, the liver gets worn out through normal wear and tear in its function as a sense organ, just as the eyes do. Because of this deterioration, the liver becomes less and less capable of perceiving whether the food we eat is good for us or harmful. Once we have grown old, the liver helps us less and less to judge how useful the substances are that have entered the stomach. This function is no longer being fulfilled properly. When it is healthy, the liver is responsible for distributing beneficial substances throughout the body and keeping harmful ones away. When the liver begins to deteriorate, however, it can no longer prevent all harmful substances from entering the intestinal glands and the lymph. From there they are spread throughout the entire body and cause various illnesses.

This gradual drop in the vitality of the liver makes it more and more difficult for older people to perceive their body inwardly as they used to. One could say that in relation to their own body they have become blind. If you are blind to the outside, someone else can guide you and help you. But if you become blind inwardly, your physiological processes don't work properly, and soon that will lead to cancer of the intestine, the stomach, the pylorus, or to some other disorder. Then the body is no longer usable. In addition, the new tissue that has to be replaced constantly can no longer be properly integrated into the body. In other words, the soul is no longer able to work on the body as it used to, and the time comes when the body as a whole must be discarded.

Actually, the body is being given up from year to year. For example, when we slough off dandruff from our scalp or trim our nails, we discard material that has become unusable. But the forces working in us remain. However, once the body as a whole becomes unusable, these forces can no longer replace anything. Just as the nail material, dead skin cells, and so forth were discarded from the body before, so now the entire body is discarded. All that remains of the human being then is the spirit. Thus, if we understand human beings at all, we have to understand them as consisting of body and spirit. We have to recognize that it is wrong to see the human being as a merely physical being. You may want to argue now that this is only a matter of religion. But it is not just a religious matter at all. The science we pursue here at the Goetheanum clearly shows that we are not just dealing with a question of religion. Religion is supposed to comfort us in our fears by assuring us that we do not die when our bodies die. Basically, these are selfish fears, and the priests count on them. Therefore they tell us that we will not die. Here, however, we are not dealing with a religious matter, but with something eminently practical. Let me explain this.

People dissecting a human liver don't think about how important it is to feed infants properly. But those who realize how these things work will find ways of bringing up children in such a way that they become healthy human beings. It is much more important to establish health in childhood than to heal illnesses later. But people do not know anything about this, because they see the human being as nothing but a pile of tissue. Well, I believe the last example illustrates fairly well what I have been trying to say.

Let us now use a different case. Let's assume a child of school age is made to learn so much that his memory is overburdened, so that the child can't come to his senses, as it were. Yes, gentlemen, this definitely puts a strain on the child's spirit. But there is more to it than that; after all, the spirit constantly works upon the child's body. If we continue to teach and educate this child in the wrong way, for instance, by overdoing memory work, we will cause certain organs of his to harden, simply because the forces channelled to his brain will be lost to the other organs. Putting too much strain on a child's brain may lead to kidney disease. In other words, illnesses may be caused in a child not only through physical imbalances but also through the way we teach and educate.

As I said, here the matter becomes eminently practical. If we really understand the human being, we can apply proper pedagogy in our schools. If, however, we view human beings as modern scientists do, the universities will only teach what I mentioned earlier, namely, that the liver looks like this and consists of minute reddish-brown lumps of tissue and so forth, but beyond that they have nothing to say.

This science is impractical because it cannot be carried into our schools. Teachers cannot make use of such a science. But they can apply a science that tells them what a healthy liver looks like at age 30, and that to allow this healthy development of the liver they have to do certain things with their eight- or nine-year-old. pupils. Then they'll know not to demand that children learn exclusively through instruction with visual aids, but to teach them in such a way that the children's organ development is stimulated and guided properly. For instance, they will tell stories and have the youngsters retell them in a way that will not overburden their memory forces but allow them to develop at their own pace. Teachers can do this, provided they understand the human being in body, soul and spirit. Out of such insight they can educate properly.

Let me ask you now whether there is not after all something far more important than preaching comforting sermons about a supernatural world to assuage people's fears of dying when their bodies do. We do indeed not die with our body, as I have demonstrated. However, priests generally only pander to people's egotistical desire to go on living. Science, on the other hand, has nothing to do with desires, but only with facts. Once we fully grasp them, these facts make this entire matter eminently practical. If we fully understand the human being, we can carry the right impulses into our schools and apply them there.

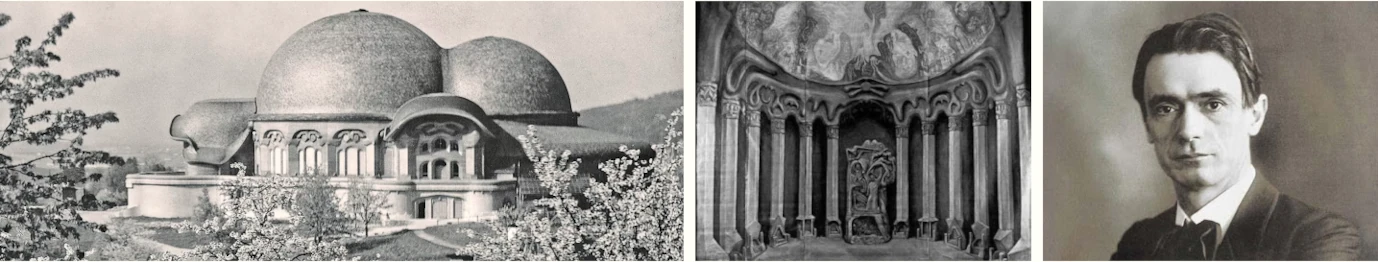

This attitude is what distinguishes the science pursued here at the Goetheanum from any other. Here we intend to gradually establish conditions that apply not only to a few scientists, but that will humanize the sciences in general so they can benefit all of humanity and help us develop in the right way.

Present-day science does not work on practical applications, except in technology and to some extent in certain other fields, such as medicine. For instance, universities teach theology or history. Well, gentlemen, let's ask whether these teachings are applied in life. A theologian cannot apply his science, not even in the pulpit, because he must preach what people want to hear. Or ask lawyers, attorneys and judges. They memorized all sorts of things for their exams. But later they will forget them as fast as they can, because the world out there is ruled by different laws. Of all this knowledge, nothing is applied to living human beings. In other words, the various disciplines of knowledge no longer have any practical relevance to life. And that is bad.

This, as you can see, leads to the formation of class distinctions between people. In life, everything living must be applied, must be used. Thus, if there is a science that can no longer be applied and is consequently useless, then the people involved in it, these scientists, are also in a sense useless; they form a redundant class in society. This is what I mean by class distinctions.

In Towards Social Renewal: Rethinking the Basis of Society, I tried to show that class distinctions are in fact also connected with our spiritual life.1Rudolf Steiner, Towards Social Renewal: Rethinking the Basis of Society (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1999). But as soon as we point out the truth, everybody calls us dreamers. However, you can see for yourselves that we are not dealing with fantasies or dreams, but with true insights that allow the various sciences to be applied in life. These insights will perhaps also reassure people about death.

Some of this may be difficult for you to follow, precisely because our school education is not what it should be. But gradually you will understand what I have been saying. Rest assured that others, even today's top scientists, do not understand me any better. If I were to present the science pursued here at the Goetheanum at Oxford University today, it would be quite different from what is being taught there and would be understood only gradually and slowly.

I wanted you to see how difficult it is to spread these viewpoints. It is difficult indeed. But we will succeed as we must; otherwise humanity will simply perish.