The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum

GA 289

The Living Organic Style I

Form: The Creative Forces of Nature

28 December 1921, Dornach

Translated by Peter Stewart

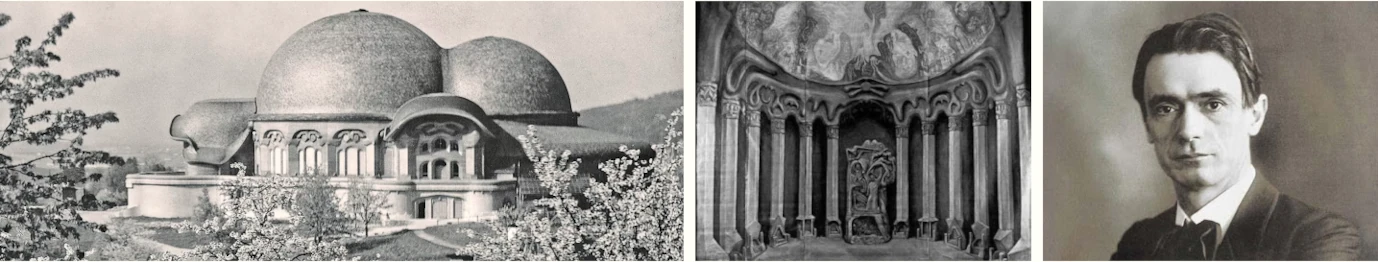

The building of the Goetheanum became necessary at a time when the anthroposophical movement had expanded to such an extent that it needed its own space. According to the whole nature of the anthroposophical movement, it could not be a question of having a building for its purposes constructed in this or that style. A movement which merely expresses itself in ideas and maxims can be wrapped up in any desired form, but not so a spiritual movement which is predisposed from the outset to let its currents flow into the whole of cultural life. The anthroposophical movement wants its impulses to flow into the artistic, religious and social spheres as well as into the scientific. When it speaks, its words, its ideas, are to come from the whole human being, and these ideas are to be only the outer language for experienced spiritual reality. But this experience of spiritual reality, of spiritual being, can also express itself in artistic forms, in outer social life, etc.

It had to be so, that in a place where that which stands behind the anthroposophical movement resounds in thoughts, resounds in words and ideas, is also revealed in the forms which surround the listeners, in the paintings which speak down from the walls.

This is how it has always been when a civilisation, a culture wanted to manifest itself in the world. The content of such a culture does not form one-sidedly, but forms a cosmic or human totality. And the individual fields, science, art, etc., appear only as the individual members of such a totality, just as in an organism the individual members appear as born out of the totality of the organism.

Therefore, the anthroposophical movement had to create its own artistic style, just as it had to create a certain way of expressing itself in ideas. The latter is still little considered today. It is, for example, necessary that anthroposophical spiritual-science should be expressed in a different way from what has hitherto been customarily contained in human civilisation.

Anthroposophy, for example, must in many respects depart from the principle, still habitually held today, of rigidly, one-sidedly, adopting a single point of view. Today, people are still often a materialist or a spiritualist, a realist or an idealist, and so on. For an unprejudiced, complete world-view this only means that when someone says “I am a materialist”, they are expressing just one side of reality, when someone says “I am a spiritualist”, they are expressing another side of reality. And anthroposophy requires all-sidedness. One is a materialist for material processes, a spiritualist for the spiritual, an idealist for the ideal, a realist for the real, and so on. Just as a tree, when seen from different standpoints, is always the same tree, but the representations of it are quite different, so the world can be represented differently from the most diverse points of view. Therefore, in the field of anthroposophy, one must simply take this path when considering some spiritual or material aspect of reality. One then chooses a point of view from which to illuminate it, one feels and thereby shows a one-sidedness, but one then characterises the same thing from the opposite point of view. So that it is often necessary—let us say—to begin a lecture by speaking from the one side, and then to let the style of the lecture flow over into a characterisation using the converse forms of thought.

But this can also be necessary in an individual sentence! And something else is necessary for the anthroposophical world-view. A world-view which adheres to the outer, naturalistic aspect, it can preferably work subjectively in, let us say, for example, one which is juxtaposed to it. Anthroposophy must make many things fluid, which are otherwise presented with rigid outlines, so that the sentence becomes elastic, inwardly mobile.

One then experiences that people call this style "terrible" because they have not got used to the fact that a particular spirituality also demands a particular form of expression. However, it also happens, and this may perhaps be said, that from some quarters, spiritual-scientific content is taken up but clothed in the stylistic form which people are accustomed to today. Then, of course, it looks like a person wearing clothes that do not fit. Such presentations of anthroposophical content, which look like a person wearing ill-fitting clothes, are not even very rare today.

But all of this is only a sign that with anthroposophy something is to be created which is not only a new instance, a new standpoint, but which is a new, complete world-conception.

And this is connected with the fact that the style, the artistic, architectural, painting and sculptural style, which had to be used in the Goetheanum, had to stand out from what had hitherto existed in the world in terms of style. In accordance with the fact that anthroposophy expresses the spiritual content of the present, which must represent progress in comparison with the spiritual content of earlier times, it was necessary to transform the old architectural styles, which were based on geometry, symmetry, a certain regularity, in short, on that which has a mathematical character, into an organic architectural style, a style which passes from the geometric-dynamic into the organic-living.

I can well understand that those who feel firmly rooted in the older styles of architecture, and who see in these older styles something which they once had brought to a certain understanding, feel that what is now departing in such a radical way from everything they were accustomed to before is dilettantish. I can fully understand that. But we had to take the risk of transforming the more mathematical-dynamic style into an organic-living style.

This may still have happened as imperfectly as possible today, but a beginning had to be made. And it is as an expression of these efforts that the "Goetheanum" confronts you.

Whoever approaches the "Goetheanum" from any direction will already find in its outer form that it is, without falling into abstract symbolism or arid allegory, a revelation of the particular spiritual life which wants to realise itself here. This spiritual life is more concerned with the human being as an expression of the world, a revelation of the world, than earlier stages of our human civilisation have been. This is expressed in the way the building is divided into two parts.

In our present age, the human being is more dependent on sensory impressions than was the case in earlier times. In Greece, for example, human beings still had a life that perceived thoughts in the external world in the same way as we perceive only colours or sounds today, or sensory impressions in general. Just as we see red today, for example, the Greek still saw a thought expressing itself. The Greek did not have the feeling that the thought was something that they formed in their inner being, that they experienced in their inner being as separate from external reality. The separation of the human being, and with it the increase in the individuality of the human being, has progressed in the course of human evolution.

I explained this in the first chapter of my "Riddles of Philosophy". And so, it was quite natural—as I said, without symbolism, without allegorising—to perceive the building as something in two parts: as one part that contains within itself that which the human being experiences more when turned inwards, that which the human being experiences when contemplatively turned inwards, and the other part which the human being experiences when turned outward towards the world. This complete architectural idea of Dornach is not somehow thought out, symbolised, or spun from groundless thoughts, but is purely felt. It had to become so, this building, if it was thought and felt as that which should be in it. Entirely in accordance with the natural principle which I have already characterised on another occasion during these days. Just as the nutshell gets its form from the same forces which formed the nut inside, just as one can only feel that the nutshell corresponds to the nut that is inside it, so also this shell had to be the sheath for what pulsates here as art, as knowledge.

I have often used another comparison that looks more trivial, but I did not mean it trivially. I said, the building in Dornach must be like what they call a Gugelhupf mould in Vienna, pardon the expression. A Gugelhupf is a special kind of cake, a baked cake that has a special shape, baked from flour and eggs and many other beautiful things. And it has to be baked in a mould. This mould must be formed in a very specific way, because it is precisely this mould that gives the Gugelhupf its shape. So, there must always be a lovely Gugelhupf mould around the cake: that is, it must be there in the first place. The cake is baked in it, so the mould must be conceived and felt in such a way that the right thing can be baked.

Anthroposophy strives to bring into a living flow the ideas which are more adapted to the fixed forms of nature, and thus to bring into a living flow the mechanical-geometric style of architecture. Therefore, when you enter the building and look at its various areas, you will find everywhere that the attempt has been made to continue the geometric-symmetrical design in such a way that organic forms or forms reminiscent of organic forms are present everywhere.

First go to the main door, you will find that there is something like an organic form above the door. This organic form is not felt in a naturalistic way, by reproducing this or that organic thing, but is based on a living surrender to organic creation in general.

One cannot, as mere naturalists do, obtain a stylistic form by imitating leaf-like, flower-like, horn-like or eye-like forms, but by bringing oneself, with one's own soul-life, into such an inner movement as corresponds to the creation of the organic. Then, when one erects a building, which of course is not a plant or an animal, then, when the whole is conceived from the organic-living, natural forms do not arise, but forms that remind one of the natural, and which nowhere imitate the natural, but which remind one of the same.

And when you have entered the building, then go through the gallery, you will find certain forms which are intended to serve as heating elements. These forms are shaped in such a way that you have the feeling that they are growing out of the earth, that there is a living growth force in them, something that is not a plant, not an animal, but something that is growing, something organic. That takes shape. That even takes shape in such a dual form. It is something like beings speaking to each other, and their mutual relationship is also expressed.

All of this, by itself, creates according to the principle of Goethean metamorphosis, which was first created by Goethe in order to gain a cognitive overview of the organic. The organic is such that it repeats certain forms, but it does not repeat them in the same way. Goethe expresses this in such a way that in the living-organic the individual organs, let us say the leaves of a plant from the bottom up into the flower, the stamens, the pistils, and into the fruit organs, are according to the idea the same, but in their outer forms, appear in the most varied ways.

When one delves into the living, one does indeed have to form things in such a way that something which is only taken hold of spiritually, ideally, can, in its external shape, form itself in the most manifold ways. This, in turn, can be led up into the artistic, whereas Goethe first of all developed it cognitively to comprehend the organs, and must be led up into the artistic if the geometric, symmetrical, dynamic style of architecture is to be transferred into the organic style of architecture. The essential thing in such an organic style of architecture is that the whole is not only a unity through the repetition of the individual parts, but is also a unity as a whole. This means that each individual element that is there, must be as it can only be in that place.

Just think, my dear guests, your earlobe—a small organ on you, it can only be at that place where it appears on the organism. It cannot be anywhere else on the organism. But it also cannot be formed in any other way than it is there. This earlobe could not be where the big toe is now, nor could it be shaped here like the big toe. In an organism, each element is in its place and can only be shaped in the way it is shaped in that place.

You will find this adhered to in this building. Wherever you look, you will feel (certainly, individual things are still imperfect, but this is the idea of the building) that the place for each individual thing is only found out of the whole and it can only be in this place.

If you look at the balustrades of the staircase with their curves, you will see that the curves are formed in a quite definite way where the building opens outwards, where nothing can be held in place, so to speak, by the forces; on the other hand, the forms dam up towards the building, they contract, as is also quite the case with the organic.

Therefore, the venture had to be undertaken to replace the columns and pillars with something organic in design. So, you see the attempt: in the staircase you see the balustrades supported by organic forms that appear as supports, which in turn are not modelled on anything natural, but which are found out of the architectural idea itself. And each individual thickening, each individual thinning, then again, the circumference of such a pillar-like structure are absolutely conceived in their size in the sense of the whole, and again conceived in such a way as they must be in their place.

I can understand that something like the two organically formed pillars in the concrete porch still seem strange to those who are not used to such things. A critic once went into this building and found it strange that such a thing should be placed there. He could only think: something must have been copied!—There is nothing imitated at all, the whole thing is just formed out of the architectural idea through original feeling. Nothing at all is copied. But the critic, who prefers to stick to the old, does not like to get involved in this creative-productive process. And so, it occurred to him: this must be an elephant's foot. But it seems that with one eye he saw an elephant's foot out there, but with the other eye it didn't seem like an elephant's foot, because as an elephant's foot it's too small for the building. What is too small for something appears rickety in the organic, and that is why he said with a strange inner contradiction: one sees "rickety elephant feet" in the anteroom!

The lower part of the building is made of concrete. Even today, when building in concrete, it is necessary to first find the forms out of the concrete material. This is something that is of the utmost importance for artistic creation: that one must build out of the feeling of the material, out of the feeling for the material. You have to build differently out of wood than out of any stone material. And of course, you have to create differently out of concrete than you would out of marble. When you form sculpturally and you form out of stone, you have to consider, for example, that which is raised in the form. When you work out of the stone, you have to work out the elevations, the convexities in particular. If you are shaping the eyes of a sculptural figure of a human being, and you have stone as your material, then direct your attention to the elevations, to the convexities, and work the whole eye out of the convexities. If you make a figure in wood, you cannot proceed in this way, then you must direct your attention everywhere to the depressions, to the concavities, and you must, as it were, carve out what is becoming deeper from the wood. This must be out of feeling. It must come from the feeling for the material.

For concrete, one must find very particular forms. Our friends the Großheintz, provided us with the site for this building, and the house that is built outside for Dr Großheintz and his family is made of concrete. For this house, this very special concrete style had first to be used, as it still can today, given the imperfections. Perhaps it is precisely in such a building that one can see the struggle for an architectural style, for an artistic style out of the material.

This aspiration was therefore the basis for the lower part of the building, which is made of concrete. The upper part is made of wood. When you go up the stairs, you enter the anteroom. And here you can already see how the ceiling and the side walls are formed differently from what you were used to. And I would like to mention that, in accordance with this new architectural style, the details have also been given a different meaning than in previous styles. This is expressed, for example, in the treatment of the wall.

What is a wall in buildings of the past? That which closes off to the outside. Here the wall does not close off to the outside, here the wall becomes, to a certain extent, transparent to feeling, it does not close off, but opens feeling to the vastness of the world. There is a profound difference between the formation of the wall as we have been accustomed to it up to now and the formation of the wall here. Everywhere else, the formation of walls closes you off from the world. But here you should have the feeling that you are not closed off. Just as you can see through glass, you feel artistically through the forms that are artistically created, and you feel in harmony with the whole cosmos.

We were therefore able to use artificial lighting for the entire building. One might have the feeling that compared to the open buildings of Greece, something like this, which reflects artificial lighting, is like a closed off cave. Well, that may be, but that is due to the conditions of modern life. We are not within the culture of ancient Greece.

But if on the one hand, as is always the case in anthroposophy, one accepts our present civilisation, if in this way one relates quite positively to our present civilisation, then one must in turn also draw on all the consequences of this civilisation. That is why the walls here do not close off, but open one in the spirit to the whole cosmos. Even the paintings on the ceilings should not be such that they merely shine inwards with what they express in their colours, so that one merely has a painted ceiling that tells one something inwards. That should not be. Such a ceiling is first thought of in this way: there is the ceiling, there is the human being. It is painted in such a way that what is painted confronts you. That is not the case here. Here the colour is placed on the wall for the purpose of looking through the painting and having a connection with the whole cosmos. This is carried through to the physical form. You can see it in the windows that close off the building down here.

These windows are designed in such a way that they are created from single-coloured glass panes according to a method that one could call glass engraving: a single-coloured glass pane, from which the form is carved out with a diamond bit. This sheet of glass, when it is finished and placed somewhere, is of course not a work of art, any more than a score is a work of art. Only when it is put in its right place and the light of the sun shines through, then the work of art is there. Only with outer nature, with the outer world, does it make sense.

And so, it is with all the details here: they only have meaning together with the whole world, with the totality of the world. There is no need to ramble on in thought, interpreting this or that in this or, that way. One should feel, completely naturally, naively, then one will find one's way best here in this building. Because that's how the whole thing is felt. Better still than to speak of the architectural idea of Dornach, I could speak of the architectural feeling of Dornach.

It has been said many times: "Up there on the Dornach hill, there is a building with all kinds of symbols.” There is not a single symbol here. Everything is poured out in artistic forms, everything is felt, nothing is thought. However, all kinds of symbols live in the imagination of some people. Yes, I could also imagine that some anthroposophists, who still have some theosophical airs about them, have even been annoyed by the fact that there is no symbolism here at all, that nothing symbolic can be spun from fantastic thoughts here, but that everything is to be understood in a purely artistic way.

It was precisely on this occasion that the real way in which the anthroposophical impulse streams into art had to be shown. First of all, a movement of this kind, which leads to the spiritual, is naturally predisposed, as is the case with sectarian movements, to seek a meaning, an inner meaning in everything.

You experience the most amazing things there. We have performed mystery plays in Munich, in which characters appear, created characters, which one should understand as they walk across the stage. I was asked whether this character in these plays meant the etheric body, another manas, another buddhi. Yes, there are even treatises that have emerged from the theosophical movement, where "Hamlet" is interpreted in such a way that the individual characters, Hamlet himself—mean this or that: one character is the etheric body, another the astral body, another manas, another buddhi. Please forgive me for not being able to explain this in detail with regard to Hamlet, for I have never been able to really read through such a treatise.

And so, it was naturally also something unfortunate that one came into the various anthroposophical working groups where there were still theosophical airs and graces, and one found all kinds of symbolic designs, black crosses with seven red splotches, which were supposed to represent roses, trafficked all around. One imagined there was something great about it! The whole thing was enough to drive one crazy! But these are—one might say—the dross that first brings forth a movement. That's what it's all about, that real artistic feeling came out of all this dross, that something was attempted in which there is nothing at all of a pale symbolism, of an empty allegory, but where at least the attempt is made to shape everything artistically.

It is precisely the artistic that then becomes natural. You can see that in these columns.1See the illustrations in Der Baugedanke des Goetheanum. (Philos.-Anthrop. Verlag). Column capitals are usually constructed according to the principle of geometric repetition. Column capitals usually repeat themselves. An organic style of architecture does not allow this. How did these column capitals, the architraves above them and the plinths, come about? They came about through the real incorporation of the principle of organic growth.

Here at the entrance—the simplest capital: a form is attempted that descends from above, another form that comes up to meet it. But all this is not thought out, but every surface, every line of the form is felt. And if one advances from the first column to the second column, and looks at the capital: it is the same feeling translated into the artistic, to which one must devote oneself to the sense of Goethean metamorphosis, when one has the simply formed leaves at the bottom of a plant and must find the transition to the leaves somewhat higher up. It reshapes itself, metamorphoses itself. And so that which descends from above to below as a form, which strives from below to above, comes into movement. And from the first capital came the second. And as the growth continues, as everything differentiates and the differentiated in turn harmonises, the third form arises from the second entirely in accordance with feeling, and so on, up to the last capitals.

But if you look at these capitals, you will see that they really represent artistically that which appears so distinctly in abstract thoughts in the modern worldview: evolution, development. The second capital develops from the first, and so on.

But one peculiarity confronts you. If you look at the successive capitals, it contradicts the abstract idea of evolution, as it is often expressed. You will also find in Herbert Spencer, for example, the idea of evolution expressed in such a way that the first simply differentiates, then integrates again. But that is not how it is. That contradicts the natural course of evolution. Whoever delves into natural evolution will find that evolution rises to certain complicated forms, then again becomes simple, and the perfect is not that which is the most complicated, but the simple into which the complicated has again been transformed. If I am to represent this in a simple way, I would have to represent it as follows: The middle form is the more complicated, the last form is the most perfect. You can see this, for example, in the evolution of the eye. The eyes of the lower animals are relatively simple, undifferentiated. In the middle series of animals, you find very complicated eyes, with the blade process and the fan inside the eye. These organs are again dissolved inside the human eye: the human eye is more perfect than that of the lower, the middle animal stage, but again more simplified. That which is in the middle stage is also spiritually within in the simplified form, but the perfect stage is again simplified for external observation. This simplification, however, is such that, as is the case with the capitals of the columns, with the architraves above, one feels in the simple that it has become, that it has been infused with that which was complicated.

I did not arrive at this design—if I may make this remark—when I worked out the model of this building, by trying to reproduce this abstract thought, which I have just expressed, externally in a symbolic way, but I arrived at it by surrendering myself to the creative forces of nature and trying to form something out of the same creative forces from which nature itself shapes. And that is how these forms came into being.

The most important thing that one encounters in the process is this: one creates quite naïve forms out of feeling. When they are finished, they show you all kinds of things that you did not intend to put into them at the beginning, just as natural forms show you all kinds of things that you discover in them. If, for example, you take the simple forms of base and capital there, and you accordingly make them somewhat elastic, then you can put the convexity of the first form into the concave part here. What is convex there is concave here, what is concave there is convex here. So that I later concluded—I did not intend it—that in terms of convexity and concavity the first column corresponds to the seventh column, the second column to the sixth column, the third column to the fifth column, and the middle one stands for itself.

That is precisely what is characteristic of artistic creation: that what one initially has in the mind is not everything that one then puts into the object. One is actually outside of oneself when creating artistically. One has only a little of what the creative forces are in one's consciousness. You create with the little that is alive, which then goes into the material. But what emerges surprises you, because you don't actually create alone, because you create together with the productive forces of the cosmos.

And purely out of feeling, the individual parts then acquire the character by which they fit into the whole, just as the members of an organism fit into the totality of the organism.

Look at this lectern here. You must feel, when you look at it, that it is a continuation of what proceeds from the mouth as the spoken word: there the words come down to you, but these forms say the same thing.

And again, if you take the columns as they are leaning here and think further about their form, if you combine them here: then the combination again becomes what stands here as a lectern. On the one hand, it leans towards the auditorium, on the other hand, it is a conclusion of what is present in the auditorium. The individual forms are conceived on this basis. However, the geometric-mathematical style of older forms is thereby transformed into a spatial-musical quality. But that, in turn, means something for human evolution, that the geometrical gradually passes over into the musical, so that the musical also confronts us in space.

However, if one wants to grasp this idea in its full livingness, one must not attach too much importance to the fact that the musical can be expressed in mathematical formulae. As a one-sided abstract scholar, one can be delighted when, let us say, a sequence of tones can be expressed by their mathematically calculated pitches and tonal ratios; one can feel that one has only now translated it into real knowledge. One can also feel it differently. One can also feel that when one has transferred the musical experience into the mathematical, one has buried the music, and that one finally has the corpse of the musical in the mathematical formulae.

These things must really be taken seriously here. The cognitive must be lifted up into artistic experience. Only by attempting this could these forms come about.

This Goetheanum is already felt to accord in many ways with Goethean impulses, but not according to the Goethean impulses that died with Goethe in 1832 within the physical world, but according to the impulses of that Goethe who is still lives today. Not as he is, however, according to the sense of ordinary Goethe scholars, but he is truly the reality of Goethe. For today's Goethe scholars, the very name "Goetheanum" is an abomination. One can understand that. The most one can do is to reply in private that everything that exists today as the "Goethe-Bund" and the "Goethe-Gesellschaft" is in turn—well, in private, you don't have to bring it out in the open—quite fatal to you. But something should be felt here of what Goethe meant when he travelled to Italy, out of a deep longing to find more intimate artistic impulses, to find the real essence of art. After looking at the works of art he saw in Italy, still feeling the after-effects of the Greek artistic principle, he wrote to his friends in Weimar: After what I see here in the works of art, I believe I have discovered the secret of Greek artistic creation. The Greeks followed the same laws in their artistic creation that nature itself follows.—And the pure abstract philosophy, which to his delight he encountered in Weimar through Herder, from the works of Spinoza, e.g. from the work "God" by Spinoza, this spiritual, essential quality in the world, this is what Goethe felt when he was confronted with the ideal works of art, and he wrote to his friends: There is necessity, there is God. And among his sayings we find the characteristic one: To whom nature reveals her open secrets, feels a deep longing for her most worthy interpreter, art.

That which appears in forms can be the same for a completely contemplated artistic impulse as that which expresses itself in thoughts. Only then the thoughts must be full of life and the forms must breathe spirit.